Tim Burton’s live-action remake of Disney’s Dumbo does a disservice to every part of that phrase. It’s a Tim Burton film with a fraction of the visual whimsy and comedic timing, and with only the most pro-forma of his pet misunderstood-misfit thematic concerns. It’s a remake of a Disney classic that takes a simple parable of an awkward elephant learning to fly and makes it about a struggling troupe of circus misfits — looking for all the world like sad, boring performers cut from The Greatest Showman — that somehow manages to lose track of Dumbo himself for long stretches of time. I spent the first moments of the film straining to like it. I was charmed by Danny DeVito’s ringmaster; he plays it as a disheveled conman who’d love to go legit if only he could afford it. (He also sings “Casey Junior” under his breath as he stumbles back to his bunk. That’s cute.) I liked Colin Farrell as a freshly one-armed WWI veteran returning to his old stomping grounds to reunite with his precocious backstage kids (the adorable — and Burton-eyed — little Nico Parker and Finley Hobbins) and piece their family back together. It’s a fine echo of what little baby CG Dumbo is about to go through. But to find “Baby Mine” didn’t quite cue the waterworks for me was a first warning sign. After the promising opening, the plot set in motion here all happens too easily, tromping from expected beat to expected beat as Ehren Kruger’s screenplay goes into the most basic family film beats of easy believe-in-yourself symbolism and repetitive crisis-resolution shaping in every scene. Only Burton’s valiant visual attempts to spark life — fine Colleen Atwood costuming filigree; Busby Berkeley circus choreography; a striking bubbly Pink Elephant sequence; an Art Deco amusement park that often looks more Tomorrowland than the film’s ostensible 1919 period setting — briefly keep the film from just laying there dead on screen. The eventual conflict involves the scrappy circus facing a takeover from a fancy entertainment industry huckster (a game enough Michael Keaton who nonetheless doesn’t have a chance to cut loose). The guy is bent on taking over and commodifying anything he can, growing through expansion and losing the heart of the family entertainment biz in the process. Thus the only truly interesting part of this whiff of a picture is that Disney somehow allowed the movie to have a greedy Walt Disney type as a heartless showbiz businessman villain and stage a triumphant fiery finale in which a proto-Disneyland goes up in smoke.

Thursday, March 28, 2019

Saturday, March 23, 2019

Mirror Mirror: US

Get Out was a brilliant directorial debut for writer/performer Jordan Peele, moving behind the camera after a great career in sketch comedy. It was an engaging entertainment: a horror movie with a deep sociopolitical engagement that was somehow both the driver of its premise and its source of laughs that catch in the throat. It was deadly serious, but worn lightly, with every setup pleasingly paid off. Now here’s Peele’s follow-up: Us. Unlike his first feature, this fright show is tantalizingly unresolved, dramatically ambiguous where the other was crystal clear, and with a slowly developing thematic conceit where the other proceeded plainly declaiming its theses. But that doesn’t mean the plot is a puzzle to be solved. The exact point its high concept can no longer be explained is the very point the movie leaps into the purely metaphoric as a troubled and unsettled vision of both the dark reflections of ourselves we can no longer ignore lurking underneath our society, and of the depraved deprivation that makes comfortable upper- and middle-class lives possible. The puncturing of those boundaries is the point: how unsettling, frightening, and destabilizing it is to confront this darkness when it can no longer be ignored.

We start in 1986, where a little girl wanders away from her parents at a Santa Cruz boardwalk, moseys into a funhouse that suffers a power outage and, stumbling in the dark, meets another little girl who looks exactly like her. Cutting on this moment of bewildered fright, Peele takes us — after a mesmerizingly simple opening credits sequence — to the present day, where this distant childhood trauma exists in the grown woman (Lupita Nyong’o) only as a faded dark cloud. It’s kicked up by her vacationing family — sweet dope husband (Winston Duke), teen daughter (Shahadi Wright Joseph), young son (Evan Alex) — heading to a Santa Cruz beach house. The place carries ominous associations for her, especially as her loved ones convince her to meet friends (a hilariously sniping shallow family played by Elisabeth Moss, Tim Heidecker, and Cali and Noelle Sheldon) at the very beach and boardwalk that was the site of her doppelgänger sighting. Eventually her unease that underpins the warmly funny familial hangout scenes is proven correct when, that night, a family of doppelgängers stand silent, dramatically backlit, at the end of their driveway. (At this point, our four leads develop remarkable, distinctive doubled performances, as gifted and eerie and convincing as you’re ever likely to see.) As the movie slinks into scary home-invasion, slasher-film machinations expertly, chilling staged, these mysterious characters — looking malnourished and eerily unkempt, clad in red jumpsuits and wielding sharp scissors — move with precise, eerie, controlled movements. They communicate with guttural howls. It put me in mind of the 1896 Paul Laurence Dunbar poem "We Wear the Mask": "This debt we pay to human guile;/With torn and bleeding hearts we smile,/And mouth with myriad subtleties."

The frightening, violent doubles reflect their better selves as if in a funhouse mirror. This is what our main characters would be if their comfortable lives were instead ones of neglect and pain; they've come to take their place. It’s scary stuff, potent to find the seemingly unstoppable forces of your destruction look just like you. Peele escalates the tension with an expert eye and razor-sharp script, becoming a litany of suspense and violence (a shame it’s a stretch to say it’s nearly a jeremiad to Get Out’s parable?) that plays off the character dynamics we so thoroughly learn and enjoy in the opening setup. (This is also the welcome wellspring of perfectly timed and executed comic relief.) The payoff is to deepen the characters through action as the film grows complicated, not through twists, although it has a few, but through challenging our assumptions and double-knotting the thematic concerns until it reflects a host of destabilizing questions. To discuss further the implications of its startling, evocative, resonant images would be to spoil the surprise and the fun. Let me just say this is an enormously entertaining, precisely controlled film. It builds, one expertly crafted sequence after another with nary a wasted image or line, until it becomes a complicated, richly developed, long-lingering jolt. At what cost do we survive? What will we do to get it? And what does it mean for us to deserve that survival? It leaves us with an expansive, haunting final image not unlike Dunbar's poem drew to a close saying, "We sing, but oh the clay is vile/Beneath our feet, and long the mile;/But let the world dream otherwise..."

Tuesday, March 19, 2019

Begin Again: NANCY DREW AND THE HIDDEN STAIRCASE

If a movie is released and no one notices was it even there? To take a detour for a moment: Too often the broad popular online film discourse is just film nerds talking to each other about film nerd movies. Who needs their umpteenth Marvel ranking or trailer analysis or an ending “finally EXPLAINED!!”? (Whatever that means.) They make the old “all thumbs” Film Comment argument about At the Movies look quaint, considering the new normal of hyperbolically aggregated press releases and bubbly ahistorical popcorn chatter makes At the Movies look like Film Comment in comparison. All this is just to say hardly anyone in film circles will tell you Warner Brothers' latest attempt to do something with the rights to Nancy Drew happened at all, or even that it's not bad for what it is: slight, cute, pleasant, girl power sleuthing. The exceedingly mild and unassuming Nancy Drew and the Hidden Staircase — so unassuming the studio itself barely seems to have noticed it turned up last weekend — is a modern reworking of Carolyn Keene’s long-running, occasionally-updated Depression-era teen detective books. Now that mostly means adding cell phones. This new version is a brightly lit, simply staged little movie following Nancy and her father moving from Chicago to a small town where her big city social justice spirit can do some good, and eventually leads to her exposing a Scooby Doo-level trick being played on a sweet old lady (Linda Lavin). Nancy is introduced skateboarding down Main Street to a bubblegum pop song, before getting asked by a new friend for help getting back at a bully. Revenge? No, “restorative justice,” Nancy says with giddy righteousness only a relatively carefree 16-year-old could muster. She's charming. A sweet rule-breaker in pursuit of truth and justice, it’d be hard not to hope she’ll succeed at whatever she puts her mind to, and even harder to think she won’t. She’s played by Sophia Lillis (the best part of the boring It movie lots liked a couple years ago) as a totally normal clever teen, using her smarts and her likable low-key charm to make friends and disentangle small-town conspiracies. Director Katt Shea (The Rage: Carrie 2) and screenwriters Nina Fiore and John Herrera (The Handmaid’s Tale) take a break from their usual heavier adult-oriented genre fare for a simple, clean-cut, clear-minded, easy narrative. As Nancy is drawn into solving the old lady’s plight, it is resolved at just the right level of complexity and speed for its intended audience — its the sort of thing you’d hope would be seen by elementary aged kids and their grandmas. There’s just enough soft-spoken kid-friendly personality to make the characters almost lifelike. And the movie is just engaging and chipper enough to fit comfortably alongside its closest competitors: the better Disney Channel Original Movies. It does basically what it says on the tin, whether anyone noticed or not. I'd rather have a sequel to this than Branagh's Poirot.

Sunday, March 17, 2019

Road to Nowhere: TRANSIT

Christian Petzold’s Transit is a story of refugees fleeing fascist forces that are taking over Europe. A German man (Franz Rogowski) sneaks out of Paris just ahead of a crackdown of some kind. He’s headed to Marseille, where he’ll wait for papers he'll need to flee somewhere safer — maybe Mexico, or America — or, failing that, he'll hike over the mountains. In this port city, he’s mistaken for a dissident writer whose immigration paperwork has already been completed. While he waits for his ship to come in, he’s surrounded by others stuck in the red tape — long lines, jumbled belongings, fraying relationships, dwindling resources. He sees the same faces again and again — a woman left stranded with two enormous dogs; a conductor; a doctor; a bartender; a soccer-loving boy and his deaf-mute mother; and a woman (Paula Beer) awaiting the arrival of her husband, a writer who promised their paperwork would be waiting for them. Pulling setup and incident from Anna Segher’s 1944 novel, Petzold’s film of people waiting in hope of exit visas could easily have fallen into a Casablanca riff, plumbing the familiar tropes of World War II fiction for its impact, much like his last film, the heartrending straight-faced melodrama Phoenix, used a rubble-strewn post-war 40’s landscape for its wickedly clever emotional twists. (Maybe Soderbergh in The Good German mode would’ve done Transit that way.) Instead, Petzold moves the book’s narrative essentially unchanged into something like present day, or maybe very near future, France. The image of modern cars and contemporary clothing, of current cruise ships, of militarized police, creates a haunting frisson of disjunction. If we saw this story, an episodic collection of displacement and strife slowly escalated through mistaken identity and competing loyalties, in vintage costume and historical affect, it’d be easier to contain in a safely time-stamped box. Here the danger, the quotidian responses to geopolitical strife, is both inextricable from the premise and a constant background given. It’s familiar and strange; it has happened before and can happen again — fascists marching in the streets. And yet Petzold hardly foregrounds this. He coaches his cast to give inscrutably troubled performances, portraying people hesitant and stumbling towards possibilities that may never come to fruition. It becomes a film of waiting, of people caught between where they’re going and where they’ve been, making connections to soothe their conscience or merely grasping at the last vital strands of humanity and compassion before the world forecloses their opportunities. Their lives have been smashed apart. They feel they just have to get on a boat and away from their broken homelands to start whole again. Would that it were so simple.

Saturday, March 16, 2019

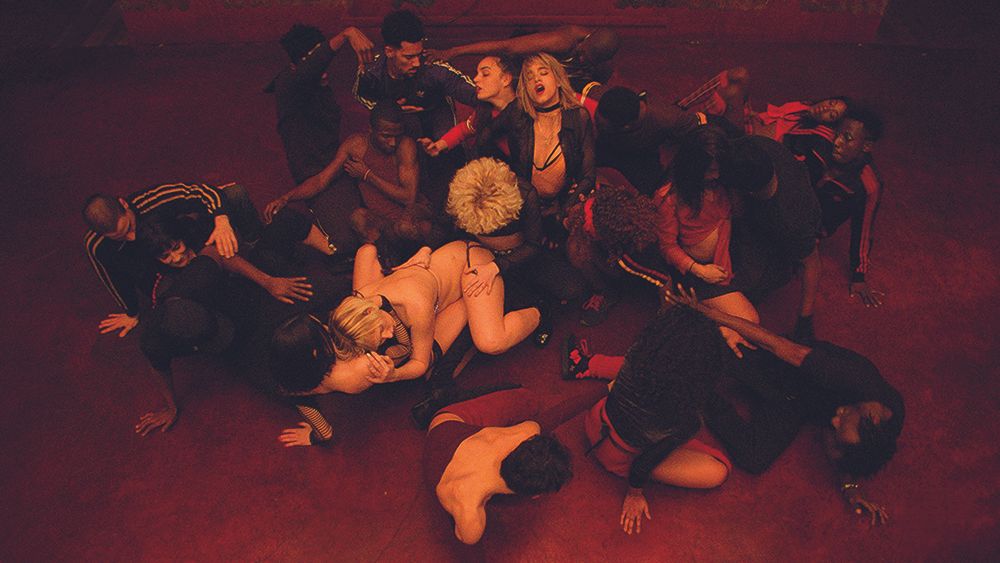

Noé Out: CLIMAX

Climax, the newest effort from French provocateur Gaspar Noé is playing at a multiplex near me. Presumably the long reach of the brand name pop art-house outfit A24 got it there. The theater’s showtime guide has it classified as horror. I’m not sure that’s exactly right, but am sure it was probably what caused at least a few of the disgruntled moviegoers to check it out in the first place. I’ll give the theater and the unhappy audience members the benefit of the doubt, though. It’s certainly a nightmare and, past a climactic tipping point, almost deliberately unwatchable, its final sequence shot upside down with a swirling camera tight on the floor in a room lit only with a flashing red light. But the way there is a delirious descent. It’s at first a movie about a dance troupe celebrating their first few days of practice with a raucous party. They’re rowdy and excited and on the prowl, a dense tangle of bodies in motion looking to drink, dance, and hook up. For a good long while it’s a stunning dance picture of inventive choreography and toe-tapping beats intercut with dancers paired off for often raunchy gossip. Alas, someone spiked the sangria, and the group falls slowly, then all at once, into a manic haze of panic, abuse, violence, and sexual advances, all set to an unrelenting club beat that pulses, pulses, pulses. Against the constant thump, thump, thump of the film’s backbeat — fading only when the long, swirling, canted, topsy-turvy takes slide down dingy corridors away from the dance floor before crawling back in agony and ecstasy — bodies writhe and dance, the thin line between beauty and disgust crossed early and often as the drugs take hold. A Step Up it’s not. It’s a film of mesmeric intensity and movement, the camera as restless and increasingly deranged as the impressive physicalized performances of a game and athletic cast — most recognizably, for American audiences, lead Sofia Boutella of Kingsman, Atomic Blonde, and Tom Cruise’s The Mummy. Noé tracks their descent into hellish mass delusion. He presents a tiny, increasingly claustrophobic group as a small sample of society that needs only the slightest push, the barest permission to shed inhibitions, to totally fall apart, for hidden desires and ugly impulses to tumble forth. It’s chaos.

Noé’s film is loud, unrelenting, an escalating litany of depraved acts and solipsistic pleasure-seeking expertly timed and brilliantly arranged for complicated camera moves, acting and dancing as one. Some characters fall into themselves in zombified repetition or self-harm, while others burst forth onto others, clawing and grinding and kissing and even, in the end, killing. It’s the sort of upsetting film where one character admits she’s pregnant and another has someone locked in a breaker room, and still another has an overbearing overprotective brother, and you start dreading the worst case scenarios, knowing there’s a good chance it’ll get to them eventually. (There’s also a shoving match near an open flame that put in mind of the immortal lyric: “Somebody call 9-1-1/Shawty fire burning on the dance floor.”) That this is nonetheless Noé’s tamest film would be news to those poor unprepared multiplex audiences. Unlike his earlier provocations like the sticky Love 3D, or hallucinatory Enter the Void, or assaultive Irreversible, there’s hardly an explicit sex scene or extended unbroken-take attack to be found. Nonetheless, he’s up to his usual concussive filmmaking tricks, throwing puzzling title cards and percussive editing into the mix, tracking his characters’ devolution with single-minded intensity while always reminding us that he’s the mastermind in charge of all this nastiness. It’s a real intense piece of work.

Friday, March 15, 2019

Lung Patients in Love: FIVE FEET APART

The latest teen weepy romance to play at something closer to realism than dystopia is Five Feet Apart. Set entirely in a hospital, mostly in a row of three rooms where teens are getting cystic fibrosis care, the movie creates its own little world of medical jargon and warm lighting. It’s its own sort of fantasy — shorn of insurance discussion, and with grief-stricken parents kept artfully to visiting hours, while the nastiest infections and fluids are left carefully off-screen — creating a closed world where a girl (Haley Lu Richardson), her gay best friend (Moises Arias), and the hot new guy (Cole Sprouse) can spend all day and some nights together, growing closer despite their medically-required need to stay apart. That some of the bonding takes place over FaceTime and texts while they're isolated from one another brings it one step out of the hospital and closer to the teen audience’s daily lives, while foregrounding how alone yet not alone the disease has left these kids. Because the girl is a YouTuber chronicling her fatal prognosis’ progression through her life, we get plenty of real detail about the disease, admirable primers and, undoubtedly, valuable representation for those so afflicted. But the movie, as directed by Jane the Virgin’s Justin Baldoni and scripted by the book's co-authors Mikki Daughtry and Tobias Iaconis, is gauzier than it is unflinching, and more manipulative and sentimental than it is unsparing. It may be sensitively built around a real issue, and confidently buoyed by actors committed to digging into the real emotions therein, but it’s also not not a YA metaphor. There’s a scene where the girl, bruised and scarred, dripping sweat, hair stringy, looks at the boy for whom she’s falling — but whose bacterial infection would be fatal for her — and he looks back lovingly. She demurs, saying she looks awful. He disagrees. Isn’t that the wish fulfillment here? The romantic core burning straight through to the heart of the audience is thus: to feel seen as beautiful and worthwhile, even at your worst. That’s valuable enough. Is the movie manipulative on this score? Undeniably. But I was happy to let it play Geppetto on my heart strings. Richardson is heartbreakingly real as she presents her character’s pain, her youthful contemplation of mortality, and her relief at finding a connection with this brooding boy — however tenuous given their diagnosis, and circumscribed their interactions given the hospital rules. Is it often possible to make such a meaningful connection with a stranger while a patient in the hospital? Well, isn’t it pretty to think so?

Saturday, March 9, 2019

The Voracious Filmgoer's Top Ten Films of 2018

1. First Reformed

2. BlacKkKlansman

3. The Miseducation of Cameron Post

4. The Ballad of Buster Scruggs

5. Private Life

6. The Favourite

7. Support the Girls

8. Unsane

9. Jeannette: The Childhood of Joan of Arc

10. Never Look Away

Special "Film Out of Time" Prize: The Other Side of the Wind

Special "Filmed Entertainment" Prize: Beychella

Honorable Mentions:

24 Frames, America to Me, Annihilation, Aquaman, Bad Times at the El Royale, Black Panther, Blockers, Burning, Cam, Can You Ever Forgive Me?, The Death of Stalin, Eighth Grade, First Man, The Hate U Give, Hitler's Hollywood, If Beale Street Could Talk, Incredibles 2, Leave No Trace, Love Simon, Mamma Mia! Here We Go Again, Minding the Gap, Mission: Impossible -- Fallout, Monrovia Indiana, Mortal Engines, Sorry to Bother You, Spider-Man: Into the Spider-verse, A Star is Born, The Tale, They Shall Not Grow Old, Thoroughbreds, Tully, Upgrade, Widows, Zama

Other 2018 bests

Other 2018 Bests

Best Cinematography -- Digital

Peter Andrews -- Unsane

Bruno Delbonnel -- The Ballad of Buster Scruggs

Alexander Dynan -- First Reformed

James Laxton -- If Beale Street Could Talk

Thomas Townend -- You Were Never Really Here

Best Cinematography -- Film

Gary Graver -- The Other Side of the Wind

Chayse Irvin -- BlacKkKlansman

Matthew Libatique -- A Star is Born

Seamus McGarvey -- Bad Times at the El Royale

Robbie Ryan -- The Favourite

Best Sound

24 Frames

Annihilation

First Man

Mission: Impossible -- Fallout

Mortal Engines

Best Stunts

Aquaman

Manhunt

Mission: Impossible -- Fallout

The Spy Who Dumped Me

Upgrade

Best Costumes

The Ballad of Buster Scruggs

Black Panther

The Favourite

Mortal Engines

A Simple Favor

Best Hair and Makeup

Bad Times at the El Royale

The Ballad of Buster Scruggs

Black Panther

The Favourite

A Star is Born

Best Set and Art Direction

Black Panther

The Favourite

First Reformed

Mortal Engines

Roma

Best Editing

The Ballad of Buster Scruggs

BlacKkKlansman

First Reformed

Mission: Impossible -- Fallout

The Other Side of the Wind

Best Original Screenplay

Andrew Bujalski -- Support the Girls

Ethan & Joel Coen -- The Ballad of Buster Scruggs

Deborah Davis & Tony McNamara -- The Favourite

Tamara Jenkins -- Private Life

Paul Schrader -- First Reformed

Best Adapted Screenplay

Desiree Akhavan -- The Miseducation of Cameron Post

Bradley Cooper & Will Fetters and Eric Roth and John Gregory Dunne & Joan Didion and Frank Pierson and Moss Hart and Alan Campbell & Robert Carson & Dorothy Parker -- A Star is Born

Nicole Holofcener & Jeff Whitty -- Can You Ever Forgive Me?

Spike Lee & Kevin Willmott and David Rabinowitz & Charlie Wachtel -- BlacKkKlansman

Audrey Wells -- The Hate U Give

Best Non-English Language Film

Burning

Jeannette: The Childhood of Joan of Arc

Let the Sunshine In

Never Look Away

Zama

Best Documentary

Hitler's Hollywood

Minding the Gap

Monrovia, Indiana

The Sentence

They Shall Not Grow Old

Best Animated Film

Early Man

Incredibles 2

Isle of Dogs

Spider-Man: Into the Spider-Verse

Teen Titans Go! To the Movies

Best Effects

Annihilation

First Man

Mission: Impossible -- Fallout

Mortal Engines

Welcome to Marwen

Best Score

Terence Blanchard -- BlacKkKlansman

Nicholas Britell -- If Beale Street Could Talk

Carter Burwell -- The Ballad of Buster Scruggs

Ludwig Goransson -- Black Panther

Justin Hurwitz -- First Man

Best Original Song

"Always Remember Us This Way" -- A Star is Born

"Hearts Beat Loud" -- Hearts Beat Loud

"Maybe It's Time" -- A Star is Born

"Shallow" -- A Star is Born

"When a Cowboy Trades His Spurs for Wings" -- The Ballad of Buster Scruggs

Best Supporting Actor

Sam Elliott -- A Star is Born

Richard E. Grant -- Can You Ever Forgive Me?

Russell Hornsby -- The Hate U Give

Cedric Kyles -- First Reformed

Tom Waits -- The Ballad of Buster Scruggs

Best Supporting Actress

Olivia Colman -- The Favourite

Zoe Kazan -- The Ballad of Buster Scruggs

Regina King -- If Beale Street Could Talk

Rachel Weisz -- The Favourite

Michelle Yeoh -- Crazy Rich Asians

Best Actor

Steve Buscemi -- The Death of Stalin

Bradley Cooper -- A Star is Born

Paul Giamatti -- Private Life

Ethan Hawke -- First Reformed

Logan Marshall-Green -- Upgrade

Best Actress

Toni Collette -- Hereditary

Lady Gaga -- A Star is Born

Kathryn Hahn -- Private Life

Regina Hall -- Support the Girls

Emma Stone -- The Favourite

Best Director

Desiree Akhavan -- The Miseducation of Cameron Post

Ethan & Joel Coen -- The Ballad of Buster Scruggs

Tamara Jenkins -- Private Life

Spike Lee -- BlackKklansman

Paul Schrader -- First Reformed

Peter Andrews -- Unsane

Bruno Delbonnel -- The Ballad of Buster Scruggs

Alexander Dynan -- First Reformed

James Laxton -- If Beale Street Could Talk

Thomas Townend -- You Were Never Really Here

Best Cinematography -- Film

Gary Graver -- The Other Side of the Wind

Chayse Irvin -- BlacKkKlansman

Matthew Libatique -- A Star is Born

Seamus McGarvey -- Bad Times at the El Royale

Robbie Ryan -- The Favourite

Best Sound

24 Frames

Annihilation

First Man

Mission: Impossible -- Fallout

Mortal Engines

Best Stunts

Aquaman

Manhunt

Mission: Impossible -- Fallout

The Spy Who Dumped Me

Upgrade

Best Costumes

The Ballad of Buster Scruggs

Black Panther

The Favourite

Mortal Engines

A Simple Favor

Best Hair and Makeup

Bad Times at the El Royale

The Ballad of Buster Scruggs

Black Panther

The Favourite

A Star is Born

Best Set and Art Direction

Black Panther

The Favourite

First Reformed

Mortal Engines

Roma

Best Editing

The Ballad of Buster Scruggs

BlacKkKlansman

First Reformed

Mission: Impossible -- Fallout

The Other Side of the Wind

Best Original Screenplay

Andrew Bujalski -- Support the Girls

Ethan & Joel Coen -- The Ballad of Buster Scruggs

Deborah Davis & Tony McNamara -- The Favourite

Tamara Jenkins -- Private Life

Paul Schrader -- First Reformed

Best Adapted Screenplay

Desiree Akhavan -- The Miseducation of Cameron Post

Bradley Cooper & Will Fetters and Eric Roth and John Gregory Dunne & Joan Didion and Frank Pierson and Moss Hart and Alan Campbell & Robert Carson & Dorothy Parker -- A Star is Born

Nicole Holofcener & Jeff Whitty -- Can You Ever Forgive Me?

Spike Lee & Kevin Willmott and David Rabinowitz & Charlie Wachtel -- BlacKkKlansman

Audrey Wells -- The Hate U Give

Best Non-English Language Film

Burning

Jeannette: The Childhood of Joan of Arc

Let the Sunshine In

Never Look Away

Zama

Best Documentary

Hitler's Hollywood

Minding the Gap

Monrovia, Indiana

The Sentence

They Shall Not Grow Old

Best Animated Film

Early Man

Incredibles 2

Isle of Dogs

Spider-Man: Into the Spider-Verse

Teen Titans Go! To the Movies

Best Effects

Annihilation

First Man

Mission: Impossible -- Fallout

Mortal Engines

Welcome to Marwen

Best Score

Terence Blanchard -- BlacKkKlansman

Nicholas Britell -- If Beale Street Could Talk

Carter Burwell -- The Ballad of Buster Scruggs

Ludwig Goransson -- Black Panther

Justin Hurwitz -- First Man

Best Original Song

"Always Remember Us This Way" -- A Star is Born

"Hearts Beat Loud" -- Hearts Beat Loud

"Maybe It's Time" -- A Star is Born

"Shallow" -- A Star is Born

"When a Cowboy Trades His Spurs for Wings" -- The Ballad of Buster Scruggs

Best Supporting Actor

Sam Elliott -- A Star is Born

Richard E. Grant -- Can You Ever Forgive Me?

Russell Hornsby -- The Hate U Give

Cedric Kyles -- First Reformed

Tom Waits -- The Ballad of Buster Scruggs

Best Supporting Actress

Olivia Colman -- The Favourite

Zoe Kazan -- The Ballad of Buster Scruggs

Regina King -- If Beale Street Could Talk

Rachel Weisz -- The Favourite

Michelle Yeoh -- Crazy Rich Asians

Best Actor

Steve Buscemi -- The Death of Stalin

Bradley Cooper -- A Star is Born

Paul Giamatti -- Private Life

Ethan Hawke -- First Reformed

Logan Marshall-Green -- Upgrade

Best Actress

Toni Collette -- Hereditary

Lady Gaga -- A Star is Born

Kathryn Hahn -- Private Life

Regina Hall -- Support the Girls

Emma Stone -- The Favourite

Best Director

Desiree Akhavan -- The Miseducation of Cameron Post

Ethan & Joel Coen -- The Ballad of Buster Scruggs

Tamara Jenkins -- Private Life

Spike Lee -- BlackKklansman

Paul Schrader -- First Reformed

Friday, March 8, 2019

mid90s: CAPTAIN MARVEL

What is there to say? Captain Marvel is the latest entry in the Marvel Cinematic Universe. At this point you know if you like this sort of thing — eighty minutes or so of quips and exposition followed by thirty to forty minutes of CG crashbangboom and a tease for future entries. Me? I like the formula well enough, always less than the rabid fans, but sometimes more than the consistent detractors. This one stars Brie Larson as an amnesiac pilot who woke up as an alien super-warrior. Much like the MCU itself, Larson is sometimes charming as all get out, and other times a total vacant dud on screen. For her role here, she chooses a pleasantly dull middle ground that almost suggests interior life. Her super-strong jet-hands-wielding self crashes down to Earth in 1995, making this a prequel and allowing oft-creepy digital de-aging to find she and we are face-to-face(ish) with waxy younger Samuel L. Jackson and Clark Gregg. On our planet, she’s searching for the typical glowing gewgaws that’ll save or destroy the shape-shifting whatevers. It’s an excuse to do the usual Marvel thing: bright colors, smiling suspense, and glowing hero poses. It held my attention, and even entertained me from time to time. It wears its period detail fairly lightly, a few Blockbusters and CD-ROMs aside, and finds some likable spark in its lead’s scrambled memories. Co-writer and directors Anna Boden and Ryan Fleck, whose subtle, empathetic touch in small character studies like Half Nelson, Sugar, and It’s Kind of a Funny Story goes almost totally missing here, scrounge up some flashes of character that are not mere plot device. (Flashes of evocative moments in gloopy montage aside, character still mostly is plot, though.) Otherwise, Boden and Fleck mange the departments just fine, roping in the usual semi-coherent action and streamlined sci-fi designs and bringing on a nicely underplayed ensemble cast once again representative of the MCU’s usual tendency for finding overqualified bit players. (Jude Law! Annette Bening! Ben Mendelsohn!) The particulars of the experience are already vanishing from my mind like Thanos dust while I'm mere minutes from the theater as I type. But it was diverting enough while it lasted, if never as silly or involving as its best franchise siblings can be. You’ll probably read the typical corporate cultist fans overselling the picture and the predictable complainers overstating the case against it. From my perspective, it’s such a big, bland, easy shrug, I can’t imagine getting worked up about it either way.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)