Thirty-six is young enough to feel like a massive life change is still possible, but also old enough to have a lot of vivid “what ifs” that have closed off some possibilities entirely. I’m sure I’m not the first to draw a metaphor comparing living your life to catching a flight. If your childhood is the runway, and your twenties are takeoff, then your thirties have to be the point where you feel you’re at cruising altitude. You’re far enough along to relax into a routine, see the shape of the horizon, while still knowing you have a long way until you reach your final destination. What if? There’s still time. Here’s Past Lives, a wistful and fragile little movie borne aloft by those doubts and those “what ifs” as its 36-year-old characters turn inwards, and backwards, for just a few days. They’re in a blend of nostalgic reverie and deep contemplation that, together and apart, cause them to reflect on their lives’ routes so far, and the other paths that had to be foreclosed to get there.

It starts at the turn of the 21st century, where two 12-year-old South Korean classmates’ friendship is teetering on the edge of romantic feelings. They sit close in class. They talk on their slow walks home. Their moms arrange a date in the park. She cries after getting a lower grade on a test than she’d expected, and he calmly stands there, awkwardly, silently, supportive. It’s all very sweet and cute, a first blush of real, deep connection in a pre-adolescent way that arises out of affection and proximity. When her family immigrates to Canada before the next school year, they don’t see each other, they don’t speak, they don’t stay in touch. More than a decade passes. The movie’s main drama—softly spoken, precisely observed—happens in two following parts: a fleeting long-distance friendship, and a long-awaited reunion on the streets of New York City a decade after that. In their mid-thirties for the film’s present tense culmination, she (Greta Lee) is a married American, and he (Teo Yoo) has just broken up with his girlfriend back in Seoul. The emotional tension swells through the two time jumps ellipsis, empty narrative space we fill in with the context clues, and the nuanced performances in which whole decades well up through body language and eye movements, as every silence swells with the unspoken.

Though it has the raw material of overheated melodrama, the confident grace and simplicity of writer-director Celine Song’s debut feature carries off a poised empathy. It’s not building to the stuff of high drama, but of small realizations, shifts in thoughtful connection, self-knowledge, and lost potentials. It embodies the melancholy wonderings of a wandering mind, traveling back to those moments in life where another choice would’ve taken you an entirely different direction. This isn’t even a movie about regrets, per se. Her husband (John Magaro) is as well-adjusted and empathetic as you could ask. This allows for a movie about the headspace a reunion can generate—and Song’s sensitive writing and cozy filmic lensing allows for the characters to explore their complicated emotions kicked up by the grown person before them being simultaneously the tween they once knew, and a stranger they’ve never known. They see some lost part of themselves reflected back in a stranger’s eyes. The movie’s generous enough to play that out with compassionate contemplation, and the final emotional release is all the more potent for it.

Friday, June 30, 2023

Retired: INDIANA JONES AND THE DIAL OF DESTINY

The most incredible part of Indiana Jones and the Dial of Destiny is how quickly it promises little, and how thoroughly it proceeds to under-deliver even on that. The deficit of imagination starts from the first shot. Remember how Spielberg’s great adventure serials would always immediately signal their exuberant visual playfulness with clever transitions out of the Paramount logo and into the action in ways that cue us to the fun to follow? Raiders of the Lost Ark fades from the studio’s painted mountain to an actual one—a flourish announcing an exciting adventure filled with cleverness. Temple of Doom goes to an engraving on a gong—the better to tell us the following will be loud, splashy, over-the-top clamor. Last Crusade fades into Monument Valley—a Western throwback telling us it is back in the zone of a comfortable lark with real imposing danger—while Kingdom of the Crystal Skull reveals a gopher hill—the better to signify the following picture will confound expectations with a mix of the self-referential and self-critical. Dial of Destiny, a much belated sequel helmed by James Mangold, and for which the raison d’être seems to be simply to cash in on one last chance for 80-year-old Harrison Ford to wear the fedora and wield the whip of everyone’s favorite action-archeologist, does something else entirely. New corporate owners mean we first see the Disney castle. Then we see the Paramount logo, followed by the Lucasfilm crest on a black background. We then cut to: a suitcase. There’s no attempt at making it a clever fade in or even a cute match cut. It just starts. I know it seems a small detail on which to focus, but the longer the movie went on, the more it seemed to typify the whole approach. Here’s a movie that cues us right from frame one to expect less.

The only one giving his all in this fifth and presumably final Indiana Jones movie is Harrison Ford. Every unadorned close-up of his aged face is full of pathos and experience that sells years of adventuring nearing its end. He’s now mostly done with field work, on the eve of retirement from his professorship, and feeling out of place in 1969. But of course a MacGuffin from his past—an ancient Grecian dial that just might have something to do with time itself—is suddenly the source of eager hunting from an ex-Nazi (Mads Mikkelsen, perfectly slimy) who’s hoping to beat a younger rogue archeologist (Phoebe Waller-Bridge, gratingly insincere) to its enormous powers. Good old Doctor Jones is the only one who can help. Or get in their way. Or both. It takes a long time for Indiana to get back in the whip-cracking spirit, and he often is without his trademark hat. He’s really, truly tired of all this. (There's nothing on that idea wasn't said more elegantly and effectively in Crystal Skull. We're in repeat territory here.) But save the world he must, though Ford’s better at sympathetically selling the weariness and reluctance now than the hard-charging action, which is left to a de-aged CG version of himself in an interminable flashback prologue or computer-assisted stunts in the present tense stuff.

Mangold, whose Logan and 3:10 to Yuma show he can make sturdy adventure elsewhere, does this no favors by shooting everything too close, and in a phony digital sheen slathered over, while cutting quickly with modern zippy animated stunt people. Early limp chases on a train and through a parade look so false and play so low-energy it’s hard to get the pulse up to care. The Foley work might be the familiar thwacks and thunks with each booming punch and echoing gunshot, and what a treat to hear John Williams once again scoring a movie with his lush orchestrations. But the pacing is all off throughout—too smooth and routine and so blandly choreographed that it all slides right off the eyeballs in an instant. Ford is the only element that feels real, even and especially when everything’s growing flimsier around him. There are a few fine gambits here—the fantastical final act, especially, is bound to be divisive, though I liked it, if more for the attempt than the weak execution. But this whole movie is weak like that, simply tired and underdeveloped thorough and through. It’s loaded with clunky plot points, scarce characterization for most side characters, and with barely an interesting image, let alone a compellingly staged action beat. Previous Indiana Jones pictures were rollercoasters. This one just coasts.

The only one giving his all in this fifth and presumably final Indiana Jones movie is Harrison Ford. Every unadorned close-up of his aged face is full of pathos and experience that sells years of adventuring nearing its end. He’s now mostly done with field work, on the eve of retirement from his professorship, and feeling out of place in 1969. But of course a MacGuffin from his past—an ancient Grecian dial that just might have something to do with time itself—is suddenly the source of eager hunting from an ex-Nazi (Mads Mikkelsen, perfectly slimy) who’s hoping to beat a younger rogue archeologist (Phoebe Waller-Bridge, gratingly insincere) to its enormous powers. Good old Doctor Jones is the only one who can help. Or get in their way. Or both. It takes a long time for Indiana to get back in the whip-cracking spirit, and he often is without his trademark hat. He’s really, truly tired of all this. (There's nothing on that idea wasn't said more elegantly and effectively in Crystal Skull. We're in repeat territory here.) But save the world he must, though Ford’s better at sympathetically selling the weariness and reluctance now than the hard-charging action, which is left to a de-aged CG version of himself in an interminable flashback prologue or computer-assisted stunts in the present tense stuff.

Mangold, whose Logan and 3:10 to Yuma show he can make sturdy adventure elsewhere, does this no favors by shooting everything too close, and in a phony digital sheen slathered over, while cutting quickly with modern zippy animated stunt people. Early limp chases on a train and through a parade look so false and play so low-energy it’s hard to get the pulse up to care. The Foley work might be the familiar thwacks and thunks with each booming punch and echoing gunshot, and what a treat to hear John Williams once again scoring a movie with his lush orchestrations. But the pacing is all off throughout—too smooth and routine and so blandly choreographed that it all slides right off the eyeballs in an instant. Ford is the only element that feels real, even and especially when everything’s growing flimsier around him. There are a few fine gambits here—the fantastical final act, especially, is bound to be divisive, though I liked it, if more for the attempt than the weak execution. But this whole movie is weak like that, simply tired and underdeveloped thorough and through. It’s loaded with clunky plot points, scarce characterization for most side characters, and with barely an interesting image, let alone a compellingly staged action beat. Previous Indiana Jones pictures were rollercoasters. This one just coasts.

Monday, June 26, 2023

Starred Up: NO HARD FEELINGS

Jennifer Lawrence is a Movie Star. If a dozen years of good performances in all sorts of genres, including anchoring the Hunger Games franchise and her multiple trips to the Oscars weren’t enough to prove that, here’s a new strong piece of evidence. In No Hard Feelings, she takes a character that’s slightly ridiculous, in a plot that’s a bit of a stretch, in a screenplay that’s a little undercooked, and filmed in a generic style, and edited to just-the-plot functionality, and easily commands the screen every step of the way. She makes the movie worth seeing. Now that’s a star. She lifts the familiar and the awkward into something entertaining, and even finds some honest sentiment in it all.

Her character is a struggling Uber driver who gets her car repossessed, so she answers an ad placed by a wealthy couple (Matthew Broderick and Laura Benanti) who want a young woman to date their shy 19-year-old son (Andrew Barth Feldman) and “bring him out of his shell” before he heads off to college. If she can successfully seduce him, she’ll get a car. He can’t find out about the arrangement, of course. (Guess what’ll happen about an hour later?) The concept clunks and clanks as it falls into place, but Lawrence dances effortlessly across the lumpy writing and polishes every scene until it’s entertaining. Consider this exchange, in her job interview:

“I just turned 29. Last year.”

“So you’re 29?”

“Last year."

“And how old are you right now?”

“32.”

Lawrence makes lines like that sparkle with a blend of obvious half-joking deception and self-effacing sarcasm. At first, her character—though teetering on the edge of desperation—comes on way too strong, a broad burlesque of feminine wiles that purposely falls totally flat, wriggling in tight dresses and leaning into obvious innuendo. It’s only when she stops trying that something softens up inside her and she can’t quite bring herself to break the boy’s heart. Lawerence sells both aspects, a quick witted desperation turning into flailing false seductiveness becoming something low-key real and charming. She elevates the material with a quicksilver timing—when told the boy’s going to Princeton, she nods and deadpans “heard of it”—that surfaces class consciousness and real connection alike.

That the movie never quite becomes a hard-edged romantic comedy is for the better. Her boyish co-star is an endearing dork we might actually care about. His awkward charms and slow-thawing shyness are played real, and not judged. But what is judged is his cocoon of privilege. The movie’s dancing a tricky line there, and it’s Lawrence’s generous, and generally real, interplay with his insecurities and ignorance alike that makes a fine counterweight to all the ways these scenes could be played wrong. She makes it almost believable this over-the-top comic premise might leave these characters slightly better people by the end. Even when the movie takes an idea to excess—neither ostensibly comedic scene of clinging to the roof of a speeding car works, though the nude fight scene is a so-bold-it’s-funny total commitment to a bit—the filmmakers are lucky they have their star just barely holding the whole picture together.

I couldn’t quite believe that I was nostalgic for this sort of movie. Here’s an R-rated relationship comedy shaggily assembled and thinly plotted, perched entirely on the charisma of its famous lead and the general likability of its supporting cast. Ten or fifteen years ago this would’ve been par for the course—every few months you could expect one or two just like it. Now, though, when the big screen is often missing Movie Star personality pictures, not to mention comedies without guns or fantasy conceits, a movie like this is a breath of fresh air. How nice to see a movie in which the only real failing is its occasional preposterousness of behavior and some formulaic plotting. At least it’s the kind of preposterousness that’s trying to entertain at a human scale, and the formulas are old enough to feel like long-lost friends. Oh, here’s where she develops real feelings for the mark. Ah, here’s the moment when the secret’s revealed. Oh, here’s the reconciliation. How nice. That such sweetness can emerge from a filthy concept is not news, but here director and co-writer Gene Stupnitsky (in a vast improvement on his painfully awkward Good Boys) makes it feel fresh enough just by letting it happen again. It helps that he trusts entirely in Lawrence’s star power to elevate everything around her. She sure does.

Her character is a struggling Uber driver who gets her car repossessed, so she answers an ad placed by a wealthy couple (Matthew Broderick and Laura Benanti) who want a young woman to date their shy 19-year-old son (Andrew Barth Feldman) and “bring him out of his shell” before he heads off to college. If she can successfully seduce him, she’ll get a car. He can’t find out about the arrangement, of course. (Guess what’ll happen about an hour later?) The concept clunks and clanks as it falls into place, but Lawrence dances effortlessly across the lumpy writing and polishes every scene until it’s entertaining. Consider this exchange, in her job interview:

“I just turned 29. Last year.”

“So you’re 29?”

“Last year."

“And how old are you right now?”

“32.”

Lawrence makes lines like that sparkle with a blend of obvious half-joking deception and self-effacing sarcasm. At first, her character—though teetering on the edge of desperation—comes on way too strong, a broad burlesque of feminine wiles that purposely falls totally flat, wriggling in tight dresses and leaning into obvious innuendo. It’s only when she stops trying that something softens up inside her and she can’t quite bring herself to break the boy’s heart. Lawerence sells both aspects, a quick witted desperation turning into flailing false seductiveness becoming something low-key real and charming. She elevates the material with a quicksilver timing—when told the boy’s going to Princeton, she nods and deadpans “heard of it”—that surfaces class consciousness and real connection alike.

That the movie never quite becomes a hard-edged romantic comedy is for the better. Her boyish co-star is an endearing dork we might actually care about. His awkward charms and slow-thawing shyness are played real, and not judged. But what is judged is his cocoon of privilege. The movie’s dancing a tricky line there, and it’s Lawrence’s generous, and generally real, interplay with his insecurities and ignorance alike that makes a fine counterweight to all the ways these scenes could be played wrong. She makes it almost believable this over-the-top comic premise might leave these characters slightly better people by the end. Even when the movie takes an idea to excess—neither ostensibly comedic scene of clinging to the roof of a speeding car works, though the nude fight scene is a so-bold-it’s-funny total commitment to a bit—the filmmakers are lucky they have their star just barely holding the whole picture together.

I couldn’t quite believe that I was nostalgic for this sort of movie. Here’s an R-rated relationship comedy shaggily assembled and thinly plotted, perched entirely on the charisma of its famous lead and the general likability of its supporting cast. Ten or fifteen years ago this would’ve been par for the course—every few months you could expect one or two just like it. Now, though, when the big screen is often missing Movie Star personality pictures, not to mention comedies without guns or fantasy conceits, a movie like this is a breath of fresh air. How nice to see a movie in which the only real failing is its occasional preposterousness of behavior and some formulaic plotting. At least it’s the kind of preposterousness that’s trying to entertain at a human scale, and the formulas are old enough to feel like long-lost friends. Oh, here’s where she develops real feelings for the mark. Ah, here’s the moment when the secret’s revealed. Oh, here’s the reconciliation. How nice. That such sweetness can emerge from a filthy concept is not news, but here director and co-writer Gene Stupnitsky (in a vast improvement on his painfully awkward Good Boys) makes it feel fresh enough just by letting it happen again. It helps that he trusts entirely in Lawrence’s star power to elevate everything around her. She sure does.

Friday, June 23, 2023

Story Telling: ASTEROID CITY

Asteroid City is something of a skeleton key for Wes Anderson’s approach to filmmaking. It consistently tells you the whole picture is artifice all the way down—and surfaces genuine emotion on the regular anyway. That’s the Wes Anderson way. He’s always doing that—using his dollhouse designs, symmetrical blocking, picture-book precision, handcrafted effects, nesting-doll framing devices, play with aspect ratio, and deadpan witty dialogue to dig deeply into ideas and emotions that hit all the harder for having been approached slyly and indirectly. An audience can be dazzled by the parade of delights he seemingly unfolds with great whimsy, only to realize the subtleties and nuances of the earnest, deliberate intentionality behind his grand designs. Detractors who misinterpret his methods as shallow affectation or meme-worthy ticks or airless style betray only their own lack of depth.

For in a Wes Anderson movie, the apparent limits are what instead allow limitless capacity for deep contemplation. He presents us perfectly designed jewel box settings and finds his characters’ melancholies radiating, uncontainable, as they, and we, are forced to confront the messiness of art, science, family, religion, sex, violence, and everything that makes life. After his Grand Budapest Hotel found bittersweet endings in its screwball capers and romantic nostalgias cut short memorialized by a writer’s work and The French Dispatch an anthology of aesthetic reveries in a funereal tribute for a magazine editor—both pictures as political and elegiac as they are surface fizz—this new film foregrounds its form and telling even further. In so doing, it also furthers Anderson’s commitment to exploring the power of storytelling—not as a pat inspirational cliche, but as the vital stuff of human existence.

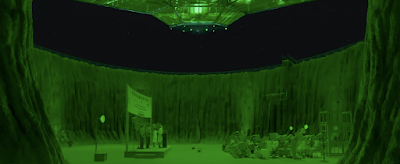

Of course a playful movie so deeply and delightfully engaged in ideas about how we explain ourselves to ourselves, and how our senses of identity and purpose are constructed, would be self-conscious as it searches for deep meaning. The movie opens on a host (Bryan Cranston) telling us we are about to watch a rehearsal for a play. In boxy black-and-white framing with theatrical lighting, we see an author (Edward Norton) at a typewriter, and the large cast assembled, and the rigging and stagehands and fakery in the wings. And then, as the story-within-that-story begins, it transforms into widescreen color full of its own artificial tricks—matte paintings, miniatures, stop-motion, and a small town where every window and door is its own proscenium arch. Here, at Asteroid City in 1955, a quaint nothing town in what’s cheerfully described as “the middle of the California, Nevada, Arizona desert,” we find a troop of Space Cadets with parents and a teacher along for a Star Gazing meetup around an ancient asteroid. The tiny motor lodge with individual cabins, next to a gas station and across from an observatory, is just another stage on which life can play out its little eccentricities.

At the center is grief, with a sad photographer father (Jason Schwartzman) telling his nerdy teen son and three cute little daughters that their mother has died. Their grandfather (Tom Hanks) is going to meet them there and drive them home, a necessity because the car just died, too. C’est la vie. It’s building a picture of a world where, no matter how much we seek to quantify and contain, people die, machines break, and the universe never loses its capacity for surprise. A mechanic (Matt Dillon) confidently tells the family that there are only two possibilities for what’s wrong with the car, only to quickly run into trouble and declare that the problem is “a third thing.” (Late in the picture, a character will matter-of-factly comment on a makeshift invention: “Everything’s connected, but nothing’s working.) More than once, a character asked “why” will respond with “It’s unclear.” And as we track back into the black-and-white world for expressionistic reenactments of the dramaturgical process, one actor will admit to not understanding his character or even the play itself. His director tells him, simply, “keep telling the story,” a phrase of advice that radiates back down into the fictions-within-fictions, and back up to us, too.

The look and tone is a fine blend of mid-century influences—Western-themed architecture and vintage technologies and designs and non-stop cowboy folk songs wafting over the town’s radios—and reflexively playful about the kinds of melodramas, both abstract and overheated, that a mid-50s writer might conjure. Knowledgeable audiences might clock the relation to the sandy sunlit widescreen staging of John Sturges’ Bad Day at Black Rock or the Technicolor small-town anxieties in Vincente Minnelli’s Some Came Running, not to mention Thornton Wilder and Samuel Beckett and Tennessee Williams and Arthur Miller and so on. (The town also has a roadrunner who chirps “meep meep,” a fine cartoon wink to foreshadow and top off the drama’s impending dusting of sci-fi elements.) And yet, for all this meta-text, we’re seeing a television special inside reenactments inside a rehearsal inside a production about a fictional town populated by dreamers and actors and schemers and scientists, every layer lost in losses and daydreams, grief and preoccupations. Perhaps an ecstatic peak of all this is when a kid performs a song, and as his classmates and teacher join in the dance, we see they’re being watched on a closed-circuit television. It’s all performances within performances.

Anderson keeps these meta-fictions spinning as an expertly choreographed and brilliantly staged nesting doll of fakery. It layers the colorful whimsy of its central story—the Star Gazers and the locals are soon trapped in town by a bizarre series of events, Close Encounters by way of Buñuel—in fictions and their tellings. It allows the movie to access both the charms of its simply plotted southwestern magical realism and its characters’ aching emotional issues, and the dizzying effort the telling. It gets at fiction itself—stories we’re told and stories we tell—and how we can get lost in it by giving ourselves over to what’s real truth within them—even kitsch, even obscure artful gestures, even when we’re unsure but “keep telling the story.” The film finds all kinds of rituals—religious sentiments, scientific methods, philosophical musings, method acting exercises, military orders, keynote addresses, backstage gossip—and notices with great melancholic empathy we’re all looking for, or clinging to, something that’ll explain our place in the vast mysteries of the universe. We need to find ourselves in the right story.

Although many of Anderson’s prior pictures allow the audience to get totally carried along in a compelling narrative and invested in characters in his controlled style, here he utilizes the grinning delights of his aesthetics of geometrical camera movements and perpendicular staging to make us always aware we’re sitting on the fourth wall. (There are even fleeting eye-contacts with the camera.) And here’s the magic: I still cared, deeply, about the characters at even the deepest levels of the fictions. There are beautiful moments of performance and writing that suddenly bring tears to the eyes with their emotional honesty. Anderson’s ability to suggest with the subtlest shifts and swiftest shimmers of interiority, whole lives behind the eyes, deep wells of regrets and confusion, longing and yearning flowers beautifully. I know I’m watching an actor playing an actor playing a character—the movie reminds us constantly—and yet, suddenly, I’m drawn in by his grief, or her confusion, or his confusion. An actress (Scarlett Johansson) in the story-within-the-story asks to run lines with a new friend and suddenly those lines (a mere half-glimpsed excerpt of another story) are somehow moving, too. It’s marvelous, the entire movie constantly making hairpin shifts between cold cerebral conceit and warm sentiment—committing fully to both and serving the thoughtfulness of each equally. The whole movie is this magic trick only a master filmmaker could pull off. It’s deeply poignant and intelligently articulated, a heady blend of heart and mind. It’s a director delivering a disquisition on his style and its intended effects, that also lands those effects with the very best of them. We’re so lucky to have Wes Anderson telling us these stories as only he can.

Sunday, June 18, 2023

Sparks Fly: ELEMENTAL

Pixar’s Elemental takes the animation studio’s formula and narrows its focus until it’s something more, well, elemental. It reminds us that, for all the high-concept world-building their films have done—from the secret life of toys, to the various monster, fish, superhero, and car societies they’ve revealed—the studio’s best at making clear, clean metaphors to explore surprisingly nuanced human emotion. Sure, they have the impressively detailed and technically accomplished animation brightly and bouncily deployed for hurry-scurry high-energy kid-friendly plots. But underneath, and driving the action, can be sadness, loneliness, longing. They find vivid, broad expressions of complicated feelings—family therapy in the guise of rip-roaring entertainments. This latest picture is in a fantasyland where earth and water and wind beings live alongside each other. Their gleaming, towering metropolis is built for their comfort, and thus the immigrant fire people must eke out a living in this space that’s literally not built for them. These beings are made of the elements, little flickering flame folks and sloshing water drops and big burly clouds animated with fuzzy lines and indistinct boundaries that drift and blur. It’s an odd sight that quick settles into sense, a shifting cartoony delight, always in flickering, bubbling, flowing motion. Director and co-writer Peter Sohn finds quick-witted detail in the background, and lets the artifice of the place just be. The movie spends next to no time world-building, and instead spends its time situating a smaller character piece in the larger whole. This isn’t as robustly imagined on the macro level as top tier Pixar, but it gets so many little details right that the overall picture is engaging throughout.

Rather than expanding its immigrant story metaphor out into a Zootopia-esque disquisition on racist implications of infrastructure planning, it’s a small family story about a struggling store, and the fiery daughter who might take over, but for an unexpected romance burgeoning. Is this the stuff of a kids’ movie? It has the sparkle and dazzle and quick wit and zippy colors of one. But these emotions are tougher, and appeal to a complicated worldview. The marriage is pure picture book metaphor—not enough to take the world of its fiction as a real place, but as a whimsical outgrowth of something real. Pixar knows how to put the ordinary in extraordinary. And so the movie rests on a daughter hoping to make her father proud, and the tension between keeping the home fires burning and finding a new path. That’s represented by a cute water guy with whom she just might have chemistry. This grounds the movie in a romantic comedy formula that plays neatly off the dovetailing of stereotypes between the characters and their elements. The fire girl has a hot temper and smoky looks that make her beau boil. The water boy is a transparently guileless fellow, and is quick to find tears in his eyes. They’re told they shouldn’t be together—it might extinguish her potential, or cause him to evaporate. But, somehow, opposites just might attract, and Pixar’s once again good at letting consequences play out, both in their families’ emotional lives, and in the way bright light sparkles through water.

Rather than expanding its immigrant story metaphor out into a Zootopia-esque disquisition on racist implications of infrastructure planning, it’s a small family story about a struggling store, and the fiery daughter who might take over, but for an unexpected romance burgeoning. Is this the stuff of a kids’ movie? It has the sparkle and dazzle and quick wit and zippy colors of one. But these emotions are tougher, and appeal to a complicated worldview. The marriage is pure picture book metaphor—not enough to take the world of its fiction as a real place, but as a whimsical outgrowth of something real. Pixar knows how to put the ordinary in extraordinary. And so the movie rests on a daughter hoping to make her father proud, and the tension between keeping the home fires burning and finding a new path. That’s represented by a cute water guy with whom she just might have chemistry. This grounds the movie in a romantic comedy formula that plays neatly off the dovetailing of stereotypes between the characters and their elements. The fire girl has a hot temper and smoky looks that make her beau boil. The water boy is a transparently guileless fellow, and is quick to find tears in his eyes. They’re told they shouldn’t be together—it might extinguish her potential, or cause him to evaporate. But, somehow, opposites just might attract, and Pixar’s once again good at letting consequences play out, both in their families’ emotional lives, and in the way bright light sparkles through water.

Saturday, June 10, 2023

Less That Meets the Eye:

TRANSFORMERS: RISE OF THE BEASTS

Let’s start by acknowledging that there’s a lot that’s just fine about Transformers: Rise of the Beasts. It has a capable director in Creed II’s Steven Caple Jr., who knows how to work with actors, deploy a needle-drop, and make the computer-generated effects for the eponymous extraterrestrial shape-shifting vehicles look passably personable and, more importantly for the Hasbro overlords, pleasingly toyetic. It has engaging leads in Anthony Ramos (In the Heights) and Dominique Fishback (Judas and the Black Messiah), who show a lot of star charisma as they occasionally overpower the flimsy material and breathe a little bit of life into cliched figures made up mainly of characteristics needed for plot utility. He’s an electronics-expert ex-military underdog with a heart of gold; she’s an ambitious museum employee dreaming of making an archeological discovery. They each get little moments up front to look something like real people before they're thrust into the explosions. That’s all fine. There’s also a decent use of a 1994 setting to allow for the plot to bump into some old tech in the set and car designs, and play era-appropriate hip-hop on the soundtrack—Digable Planets and LL Cool J get satisfying showcases. It’s also the right time period to introduce the Beast Wars characters, 90s-era Transformers that turn into animals. I can’t complain about any of that. These are good ideas deployed in largely non-irritating ways. But, as barely a sequel to the Bumblebee prequel and only vaguely a prequel to the original Michael Bay Transformers, the whole movie is pinned in by that larger overall sense of indecision.

Say what you will about Bay’s work, it makes huge decisive choices about what to show—staging the central alien robots towering over their human castmates, hurtling through action sequences shot for heft and scale. Those movies, for all their chaos and confusion, grounded outsized spectacle with a real sense of gravity and space, always filling the frame with a flurry of activity across multiple planes of perspective, placing its giants in motion against backdrops of forests and skyscrapers and small streets and recognizable architectural features to consistently place us amid the careening clashes and explosions in a state of concussed awe. Rise of the Beasts doesn’t bother. It largely takes place in wide open places or in frames that barely explore the spacial possibilities of its enormous aliens. It hops around the usual MacGuffin chase—to get Optimus Prime and his Autobots home they need to beat Unicron’s minions to the trans-warp key! Yes, the trans-warp key! I practically shouted it with them at a certain point of peak repetition—every stop on the journey loaded up with rumbling quips and bland formula. Then it ends in the usual all-CG conflict in a bland, grey field of nothing in the middle of nowhere as a portal in the sky threatens to explode the world. It’s all curiously small, holding back from the excesses of Bay’s efforts—shorn of most of his high-impact militarism, the leering objectification, and the casual prejudices, but the process has also leeched the enormity of the fireballs and visual weight. The memorable fun, in other words. It’s just a play-it-safe, by-the-numbers franchise entry where all the good ideas are buried in the vague nothing of its aesthetic choices and narrative familiarity.

Say what you will about Bay’s work, it makes huge decisive choices about what to show—staging the central alien robots towering over their human castmates, hurtling through action sequences shot for heft and scale. Those movies, for all their chaos and confusion, grounded outsized spectacle with a real sense of gravity and space, always filling the frame with a flurry of activity across multiple planes of perspective, placing its giants in motion against backdrops of forests and skyscrapers and small streets and recognizable architectural features to consistently place us amid the careening clashes and explosions in a state of concussed awe. Rise of the Beasts doesn’t bother. It largely takes place in wide open places or in frames that barely explore the spacial possibilities of its enormous aliens. It hops around the usual MacGuffin chase—to get Optimus Prime and his Autobots home they need to beat Unicron’s minions to the trans-warp key! Yes, the trans-warp key! I practically shouted it with them at a certain point of peak repetition—every stop on the journey loaded up with rumbling quips and bland formula. Then it ends in the usual all-CG conflict in a bland, grey field of nothing in the middle of nowhere as a portal in the sky threatens to explode the world. It’s all curiously small, holding back from the excesses of Bay’s efforts—shorn of most of his high-impact militarism, the leering objectification, and the casual prejudices, but the process has also leeched the enormity of the fireballs and visual weight. The memorable fun, in other words. It’s just a play-it-safe, by-the-numbers franchise entry where all the good ideas are buried in the vague nothing of its aesthetic choices and narrative familiarity.

Friday, June 2, 2023

Great Power: SPIDER-MAN: ACROSS THE SPIDER-VERSE

Plunging head first into the tangled webs of superhero canon, Spider-Man: Across the Spider-Verse tells, improbably, the best superhero story the big screen has seen in ages. It does so by turning around and directly confronting the very nature of its telling. It features one of its antagonists sounding a lot like one of those whiny fandoms that complains about every deviation from the formula, and every divergence from the previously established canon. This guy gives a serious, glowering monologue in which he lays out the idea that certain characters simply must die, because that’s the way these stories are supposed to go. They die in every story, in every timeline, to serve the same purpose. In our world, that satisfies the conservative fanboy in the audience, and, indeed, a middling serving of cameos and connections is enough to keep the whole machinery of these franchises turning. But this group of filmmakers, including screenwriters Phil Lord and Christopher Miller (The LEGO Movie) and co-director Kemp Powers (Soul) among dozens of talented collaborators, are thinking beyond that here. What Across the Spider-Verse does by placing this idea at the center of its conflict is stirring stuff—and the kind of bold, inventive, imaginative storytelling that these sorts of stories are supposed to be about in the first place.This clever eruption of animation and excitement builds beautifully off the distinctive pleasures of its predecessor, Into the Spider-Verse, that introduced us to dimension-hopping Spider-Men through the eyes of Miles Morales (Shameik Moore), a Brooklyn teenager bit by a radioactive spider. So far, so familiar to the Peter Parkers we’ve known, albeit with a cool cultural specificity that is a modern-day, teenaged, half-Black, half-Puerto Rican New Yorker. But because his special spider fell through a hole between parallel universes, it immediately involved him meeting a selection of alternate Spideys—a Peter Parker (Jake Johnson), an anthropomorphic pig, a Japanese mech suit, and so on, including a crush-worthy spider-powered Gwen Stacy (Hailee Steinfeld). That movie had its instantly lovable and sympathetic hero in Miles—as at home in his sleek form-fitting black suit as he is in Nikes and a hoodie—fitted in a stylish animated world that had a fluid hand-drawn-over-CG aesthetic complete with comic book affectations like faded overlapped multi-dot colors and zippy split-screen and text boxes with narration and onomatopoetic emphasis. The Spider-people from other worlds came trailing their own distinct styles—jagged CG and jumpy anime and inky black and white and so on. The sequel starts with Miles alone in his own universe, where he has plenty of quotidian Spidey troubles juggling school, family, and his secret identity. Soon enough, though, a seemingly dopey villain—voice with blasé nefariousness by Jason Schwartzman—opens damaging portals between universes, and it all tumbles into potential chaos again. The story quickly bests the original vision in two directions at once—digging deeper into Miles’ world and inner life, while exploding out in a dazzling variety, swirling with inventive style and cultural melange as a secret inter-dimensional squad (led by Oscar Isaac and Issa Rae) senses trouble in the multiverse.

The result is a movie that’s a non-stop visual delight surrounding its sympathetic core. Each new world feels pulled from a different designer. There’s a scratchy parchment renaissance character, a Brit punk Spidey sketched on rumpled paper and traveling via collage, stiff-armed Hanna-Barbera style vintage beings, brief glimpses of stop-motion and even live-action worlds, and, my favorites, a dazzlingly detailed Indian metropolis and a world where wet watercolor backgrounds drip expressionistically as characters try not to cry. But at the center of it is one kid, trying his best to do right for his family, his friends, his crush, and his city. And isn’t that so authentically Spider-Man? There’s genuine capital-R Romance here, in all the outsized adolescent emotions that this particular superhero has always done so well. Think about the best moments in any previous Spider-Man movie. It’s not the action, per se. It’s the beats between, where characters really matter, and the stakes are built, not out of the world ending, but about a particular person’s place in the world. This movie knows that deeply—allowing for long scenes to breathe and accumulate real investment in the relationships on display in voice performances that are universally warm and committed. For all its wild and creative action—and there’s more here in even the first sequence than we get in most full length spectacles of this size—there’s the beating heart yearning for connections. Every twist and complication as the story expands and explodes earns its weight from this source—a boy who wants to make his parents proud, impress the girl, and save, not the world, but his world. This is Spider-Man storytelling at its finest, including a great cliffhanger that left me eager for the next issue.

The result is a movie that’s a non-stop visual delight surrounding its sympathetic core. Each new world feels pulled from a different designer. There’s a scratchy parchment renaissance character, a Brit punk Spidey sketched on rumpled paper and traveling via collage, stiff-armed Hanna-Barbera style vintage beings, brief glimpses of stop-motion and even live-action worlds, and, my favorites, a dazzlingly detailed Indian metropolis and a world where wet watercolor backgrounds drip expressionistically as characters try not to cry. But at the center of it is one kid, trying his best to do right for his family, his friends, his crush, and his city. And isn’t that so authentically Spider-Man? There’s genuine capital-R Romance here, in all the outsized adolescent emotions that this particular superhero has always done so well. Think about the best moments in any previous Spider-Man movie. It’s not the action, per se. It’s the beats between, where characters really matter, and the stakes are built, not out of the world ending, but about a particular person’s place in the world. This movie knows that deeply—allowing for long scenes to breathe and accumulate real investment in the relationships on display in voice performances that are universally warm and committed. For all its wild and creative action—and there’s more here in even the first sequence than we get in most full length spectacles of this size—there’s the beating heart yearning for connections. Every twist and complication as the story expands and explodes earns its weight from this source—a boy who wants to make his parents proud, impress the girl, and save, not the world, but his world. This is Spider-Man storytelling at its finest, including a great cliffhanger that left me eager for the next issue.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)