Thursday, August 1, 2024

What Fresh Misery Is This? LATE NIGHT WITH THE DEVIL, IN A VIOLENT NATURE, MAXXXINE, and LONGLEGS

Take the surprise sleeper hit of the spring: Late Night with the Devil. It sets itself up as found footage: a doomed episode of a 1970’s talk show wherein a possessed guest wreaked demonic havoc on live television. That’s an incredible premise, and with character actor David Dastmalchian in the lead role playing a kind of flop sweat Dick Cavett, has some unctuous charms. The way the intimations of real horror build along with the chummy surreality of a bleary-eyed half-imagined midnight talk show, segment by segment, has a nice sick logic to it as well. Where the movie loses me, and keeps it from fully activating its potential, is its craftsmanship. Writer-directors Cameron and Colin Cairnes fumble all the little details—from the too-digital faux-video look, to the vaguely modern phoniness of some performances, to the too-smooth gore effects—and break their own conceit with implausible and unnecessary behind-the-scenes photography and some nightmare-perspective shots in the back stretch cut into what could’ve stayed trapped in the diegetic. The longer it went on like that, the more frustrated I was that such a promising idea was whittled away one distracting choice after the next. It’s like they didn’t have the confidence to fully commit to their own idea.

If you want to give some credit for commitment to the bit, though, look no further than In a Violent Nature. It isn’t much of a movie, but as an excuse to sit in the dark and think about slasher movies, it’s not so bad. It’s basically a knockoff Friday the 13th from Jason’s perspective, or more accurately from a third-person camera following closely behind him. The trance-like pacing includes a lot of tromping around in the woods, the distant sounds of shallow young adults carousing and camping drawing nearer as a hulking brute slowly, steady stomps toward them. The eventual kills are so grotesquely over-the-top, even by the genre’s standards, that one watches them with a sick fascination. It’s not so much about the death on display as clocking where, exactly, the wound makeup and eviscerated dummies are digitally stitched into the shots of real actors, and trying not to vomit through one’s appreciation for all that macabre hard work making it look excessive and real when someone is literally pretzeled inside out and pushed down a ravine. Writer-director Chris Nash makes a patiently punishing movie that makes the audience wait and wait, listening to nothing but the crunch of leaves and twigs underfoot as the killer’s back ambles onward to excessive violence. The plot, such as it is, is bone-deep derivative, and any glimmers of genre critique are quickly squelched out by the flat-faced slasher logic taken too seriously. For however much it had me contemplating why people, myself included, even enjoy this hack-and-stab form, it had my mind wandering to all manner of other films of its kind—both better and worse—rather than focus on the increasingly dull one in front of me.

I had a similar sense of diminishing returns with the summer’s bigger art house horror efforts: Ti West’s MaXXXine and Oz Perkins’ Longlegs. Both from reliable modern auteurs of the genre, they nonetheless fall flat in the way strong starts peter out into predictability. They’re not without their surface charms of style, but they never truly satisfy like their inspirations. West’s film is the third in a trilogy he began with his fun 70s throwback X, in which an indie porn crew is killed off on a remote Texas farm, and then continued with Pearl, a flashback to the beginning of the century where a desperate farm girl hoped for stardom and decided to murder instead. MaXXXine is in a neon-and-synths 80s L.A. and finds the imaginary actress of the title role (Mia Goth) trying to transition from porn to horror. Too bad people she knows are being killed off by a giallo-styled leather-gloved perv. It makes for a rather simplistic movie with a mystery that’s limply deployed and violence sparingly splattered. It also introduces nothing new or nuanced about its character or the doomed death-drive to stardom we haven’t already picked up. By the time we get to the weirdly routine conclusion—in which a detective played by Michelle Monaghan gets one of the funniest exits in recent memory—I was wondering what all the empty pastiche was even supposed to be saying at this point. At least Longlegs has some truly terrifying moments punctuating a thick layer of dread. It’s a dimly-lit, coolly framed serial killer procedural that slowly sinks into a satanic spell. Maika Monroe does a good Jodie Foster, and Nicolas Cage brings a typically talented and engaging push-pull between outlandishness and underplayed creepiness. His grotesquely made-up face, shrill vocalizing and halting rhythms puncture the chilly restraint of the filmmaking, warping the texture of the tone and bending the whole movie toward his evil gesticulations. That makes for a great uneasiness at play in every scene, especially when photographed in precision anamorphic tracking shots tied to a figure in the frame. But it’s all so cramped and small, and ultimately way more pedestrian, even in its nightmarish magical realism, that I spent the last third in a shrug. But compared to some of these other horror movies this year, no wonder this one hit the box office with a bit of a jolt.

Friday, September 23, 2022

Characters Welcome: PEARL and CONFESS, FLETCH

She feels stuck, and the film acutely sees the pain in the smiles she fakes for family and friends. She just wants a way out. Maybe stardom as a dancer, like in the picture shows she loves so much, is her ticket? Shame, then, that life conspires to keep her down, although her off-putting neediness and grindingly pathetic obliviousness can’t be much help. Still, she blames everyone but herself, and slowly starts to think she’d be better off without them. West, co-writing with Goth, digs into the oddities of this broken woman’s psyche, and follows on her dark path papered over with obvious falseness of Americana Pollyanna psychopathy. The screen is wide, the colors lush, the music swirling with Herrmann-style romantic strings, and the lighting bright and overpowering. There’s a gleam to the look and a glint in Goth’s eye as the poor lady starts to crack. The film’s high point is not the few bloody axings or slow-motion self-destruction of this cramped family unit, but a high-wire, close-up, one-shot monologue in which Pearl finally unburdens every nook and cranny of her conflicted emotional storehouse to an unsuspecting friendly ear. It’s a nervy, unsettled, bleakly funny, and even empathetic scene that goes on and on. We somehow care for Pearl, in all her raw vulnerability, even as the long speech winds on, digging herself deeper into a whole lot of trouble. We know her so well by then it’s hard to look away.

But for a character who’s a much more pleasant hang, check Confess, Fletch. Writer-director Greg Mottola—whose Superbad and Adventureland are also pleasant hangout comedies—once more proves not every character-based movie needs trauma to excavate. (How refreshing.) Fletch, the star of a series of dry, sly mystery novels by Gregory Mcdonald, is an ex-investigative journalist whose appeal sits squarely in how effortlessly at ease he feels bumbling into any situation, even as danger and disorder escalates. He’s just an appealing personality in a shaggy genre package. Here, played with rumpled charisma by Jon Hamm, he’s on the case of some missing paintings, which may or may not be related to an abducted Count. There’s also a murder Fletch didn’t commit, but the facts keep stubbornly implicating him anyway. This tangled web grows to involve art dealers, an Italian heiress, a few shady rich folks, a countess, a couple of cops, a yacht club security officer, and a loopy stoner. The screenplay provides eccentric characters and sequences with a charming straight-faced silliness. The repartee sparkles with wit, and the clues assemble with intelligence, while Fletch unflappably stumbles into deeper and deeper trouble while barely breaking a sweat.

It’s a character-driven comedy, in that it’s all about conversation and relationships and adult foibles and has an interesting person drawing us along through it all. He’s the sort of guy who thinks he can talk his way into or out of any situation, and probably can. He was played by Chevy Chase in two 80s adaptations, who gave the concept his own layer of smarminess. Luckily, Hamm knows he can’t out chase Chevy on that terrain, and so leans into a relaxed confidence that’s totally appealing. Here’s a movie that knows how to have a good time, giving a fun presence smart speech and a compellingly complicated mystery told so low-key that it’s more about the fun energies of a pileup of character actors (Roy Wood Jr, Kyle MacLachlan, Annie Mumolo, John Slattery, Lucy Punch, Marcia Gay Harden) circling each other until the solution half-accidentally resolves. Mottola wisely keeps this chill movie at jazzy remove, a sort of brushes-on-snare shuffle to the rat-a-tat dialogue and sparkling fizz to the complications. Fletch always has some trick up his sleeve, planning out contingencies and doling out fake names to wriggle wherever the next clue, or escape, might be found. It’s a cool pleasure to pass time with a movie that so generously lets us enjoy this enjoyable character’s company and try to think a few steps ahead with him.

Sunday, March 20, 2022

Spare Parts: TEXAS CHAINSAW MASSACRE and X

And now our most recent cycle of horror reboots comes for The Texas Chain Saw Massacre, Tobe Hooper’s 1974 genre landmark. The 2022 iteration, called Texas Chainsaw Massacre (drop the article, close the space), ignores all other attempts to continue the original story in order to claim status as a real continuation, like David Gordon Green’s Halloweens. It catches up with Leatherface, the hulking masked brute wielding the murder weapon of the title, who is about to unleash terror once again after decades sitting dormant. You see, instead of youths in a van stumbling into a murderous family’s house in the middle-of-nowhere Texas, there are social media influencers coming to his small dead-end Texas town in hopes of revitalizing it. Easy targets, no? Director David Blue Garcia, from a screenplay in part by Fede Alvarez and collaborators who did the excellently vomitous Evil Dead reboot, uses the premise to stage a predictable slasher picture that never gets out of the shadow of its vastly superior inspiration.

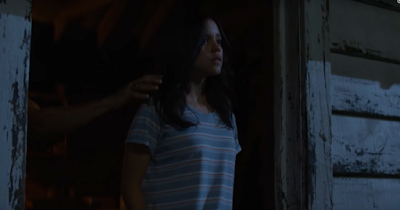

It puts in a slick effort, though. Too slick is more like it. The new cast (like Sarah Yarkin, Elsie Fisher, and Jacob Latimore) is quickly characterized as troubled and idealistic youths. They’re waiting on a bus of tech investors and streaming stars to help them buy up the town, in the process accidentally displacing the unfortunate Leatherface. Eventually they’re joined by returning final girl Sally Hardesty (Olwen Fouere), grey-haired and ready to fight, having evidently taken her lifestyle cues from Jamie Lee Curtis’ Laurie. (Isn’t it more than a little depressing that such thrilling survivors are constantly shown in these sort of follow-ups to be stuck in place waiting for a sequel well into their elderly years?) Garcia directs the ensemble through a routine number of slaughter sequences, with tons of splatter and viscera, including sloppy disembowelments and spraying decapitations, often carried out with bloody convincing and coldly detailed makeup effects that are certainly a mark of talented craft. But attempts to update its premise are laughable. One guy live-streaming Leatherface declares, “if you do anything, you’re cancelled, bro.” And there may be no more sad commentary on the drop from the original than a final moment riffing on the iconic back-of-the-pickup-truck gasp of cathartic laughing screams that trades it in for a Tesla self-driving into the sunset with its passenger staring helplessly back.

But these filmmakers run into the same problem that all who attempt to follow up the original eventually encounter. Their movies inevitably feel just like movies. Turns out, each new Massacre emphasizes all the more that Hooper’s original isn’t merely a movie, but an unreplicable nightmare. It’s a deceptively crafty work of extreme low-budget ingenuity that resulted in something that plays, to this day, as a work of filmmaking that feels less like a movie, and more dangerously real, with judicious gore, perfectly amateur performances that are plain and raw, and implied terrors so upsetting just outside the frame that the whole picture plays as if its jagged edges threaten to tear loose from the sprocket holes and burn away before our very eyes. Its smallness and its suggestion, combined with its seemingly unaffected naturalism and rough-hewn design, make it so purposely rough and unformed that it truly does feel like anything’s possible. There’s real danger in it. This latest attempt is simply a proficient gore machine, running through the motions, gliding easily down a path the original tore open. It is too neatly packaged to feel truly dangerous.

The film’s conceit locates the intersection between grungy horror and narrative porn, two types of variably disreputable filmmaking bubbling out of the midcentury indie film markets, built on teasing suspense, suggestive editing, and goading audience reactions with sudden explicit reveals. They each, in their eye-popping way, make use of what Berkeley film professor Linda Williams calls “the frenzy of the visible.” They’ve also long had the most, ahem, robust amateur scenes. Especially in the 70s’ regional cinemas (from whence we get Hooper as well as other horror-makers Romero and Craven and Raimi), both genres found purchase in the extremes of mainstream acceptability or just beyond—and, in retrospect, that both had viable theatrical models at the time is almost unbelievable to consider from their current cultural position. Back then, ambitious filmmakers could scrounge up a shoestring budget, and find their rough-hewn howls of creativity speckled with real ingenuity driven by a desire to grab attention. That’s what makes a breeding ground for greedy hucksters and thoughtful artists alike, bound together by exploitation concepts, dubious financing, and corner-cutting illegalities, ultimately becoming the foundation for the boom of American indies in the decades after.

By setting his new movie in the 70s, West sells it partially as a tribute to the entrepreneurial spirt of low-budget moviemaking. The director in the movie (Owen Campbell) says he wants to do more than give the audience what they want, experimenting with the editing “like the French do.” (West obliges, by giving X some stutter-step transitions between scenes and a beautifully ominous split-screen music montage rising action just before things go from bad to worse.) This independent filmmaker brings along his girlfriend (Jenna Ortega) to operate the sound equipment. She didn’t know what kind of movie they’d be making, and is off-put, but also a little surprised how much she likes seeing the performances in front of the camera. The smarmy producer (Martin Henderson) just wants to strike it rich, and make his fiancé (Mia Goth) a sex symbol. The other performers (Brittany Snow and Scott Mescudi) just want to celebrate something they enjoy, and enjoy sharing. West shows us the satisfaction they all take with the creativity, not just the physical act, of their art. They enjoy framing shots and talking ideas for new scenes. They own up with a frankness to their pursuits, and are eager to have their work seen by the masses. After all, they say, why not have fun before they’re too old. “To the perverts!” they toast after their first day of filming, in a sequence of cozy camaraderie that the film’s promised bloodbath drawing closer makes inescapably melancholy.

The back half of X is devoted to the backgrounded creepiness of the old couple escalating to deadly consequences. This results in a series of creatively gross murder sequences, with bodies penetrated by knives and pitchforks and nails and gunfire and…well, I won’t spoil them all. The effects are good gooey gore, with the makeup work on wounds, torn flesh, and fragmented bones cringingly well-done. And the ways West builds suspense and release with jumps and twists—some people die in exactly the way it looks like they will, while others have more sudden or surprising exits—are satisfying in a jolting horror movie style. The more we see of the elderly duo who are resentful of these beautiful young libertines and only grow more so the more they see of them—quite literally—the more it’s clear they’re acting out of deeply repressed or thwarted desires of their own. West pushes a bit too hard on the fright factor of the elderly—I’m not sure wrinkly skin and various dermatological issues are as inherently icky as the movie leans on—but their behavior makes them suitably, pathetically villainous. Everyone has their role. Overall, it’s a horror movie in love with being a horror movie, playing with tropes throughout. There’s evident delight taken in setting up a charismatic cast we hate to see slaughtered and then admire how the filmmaker pulls it off. It may be no less predictable or derivative for it, but the affection shines through every satisfying twist of the plot—and the knife.