Asteroid City is something of a skeleton key for Wes Anderson’s approach to filmmaking. It consistently tells you the whole picture is artifice all the way down—and surfaces genuine emotion on the regular anyway. That’s the Wes Anderson way. He’s always doing that—using his dollhouse designs, symmetrical blocking, picture-book precision, handcrafted effects, nesting-doll framing devices, play with aspect ratio, and deadpan witty dialogue to dig deeply into ideas and emotions that hit all the harder for having been approached slyly and indirectly. An audience can be dazzled by the parade of delights he seemingly unfolds with great whimsy, only to realize the subtleties and nuances of the earnest, deliberate intentionality behind his grand designs. Detractors who misinterpret his methods as shallow affectation or meme-worthy ticks or airless style betray only their own lack of depth.

For in a Wes Anderson movie, the apparent limits are what instead allow limitless capacity for deep contemplation. He presents us perfectly designed jewel box settings and finds his characters’ melancholies radiating, uncontainable, as they, and we, are forced to confront the messiness of art, science, family, religion, sex, violence, and everything that makes life. After his Grand Budapest Hotel found bittersweet endings in its screwball capers and romantic nostalgias cut short memorialized by a writer’s work and The French Dispatch an anthology of aesthetic reveries in a funereal tribute for a magazine editor—both pictures as political and elegiac as they are surface fizz—this new film foregrounds its form and telling even further. In so doing, it also furthers Anderson’s commitment to exploring the power of storytelling—not as a pat inspirational cliche, but as the vital stuff of human existence.

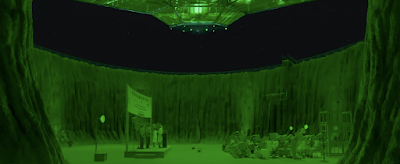

Of course a playful movie so deeply and delightfully engaged in ideas about how we explain ourselves to ourselves, and how our senses of identity and purpose are constructed, would be self-conscious as it searches for deep meaning. The movie opens on a host (Bryan Cranston) telling us we are about to watch a rehearsal for a play. In boxy black-and-white framing with theatrical lighting, we see an author (Edward Norton) at a typewriter, and the large cast assembled, and the rigging and stagehands and fakery in the wings. And then, as the story-within-that-story begins, it transforms into widescreen color full of its own artificial tricks—matte paintings, miniatures, stop-motion, and a small town where every window and door is its own proscenium arch. Here, at Asteroid City in 1955, a quaint nothing town in what’s cheerfully described as “the middle of the California, Nevada, Arizona desert,” we find a troop of Space Cadets with parents and a teacher along for a Star Gazing meetup around an ancient asteroid. The tiny motor lodge with individual cabins, next to a gas station and across from an observatory, is just another stage on which life can play out its little eccentricities.

At the center is grief, with a sad photographer father (Jason Schwartzman) telling his nerdy teen son and three cute little daughters that their mother has died. Their grandfather (Tom Hanks) is going to meet them there and drive them home, a necessity because the car just died, too. C’est la vie. It’s building a picture of a world where, no matter how much we seek to quantify and contain, people die, machines break, and the universe never loses its capacity for surprise. A mechanic (Matt Dillon) confidently tells the family that there are only two possibilities for what’s wrong with the car, only to quickly run into trouble and declare that the problem is “a third thing.” (Late in the picture, a character will matter-of-factly comment on a makeshift invention: “Everything’s connected, but nothing’s working.) More than once, a character asked “why” will respond with “It’s unclear.” And as we track back into the black-and-white world for expressionistic reenactments of the dramaturgical process, one actor will admit to not understanding his character or even the play itself. His director tells him, simply, “keep telling the story,” a phrase of advice that radiates back down into the fictions-within-fictions, and back up to us, too.

The look and tone is a fine blend of mid-century influences—Western-themed architecture and vintage technologies and designs and non-stop cowboy folk songs wafting over the town’s radios—and reflexively playful about the kinds of melodramas, both abstract and overheated, that a mid-50s writer might conjure. Knowledgeable audiences might clock the relation to the sandy sunlit widescreen staging of John Sturges’ Bad Day at Black Rock or the Technicolor small-town anxieties in Vincente Minnelli’s Some Came Running, not to mention Thornton Wilder and Samuel Beckett and Tennessee Williams and Arthur Miller and so on. (The town also has a roadrunner who chirps “meep meep,” a fine cartoon wink to foreshadow and top off the drama’s impending dusting of sci-fi elements.) And yet, for all this meta-text, we’re seeing a television special inside reenactments inside a rehearsal inside a production about a fictional town populated by dreamers and actors and schemers and scientists, every layer lost in losses and daydreams, grief and preoccupations. Perhaps an ecstatic peak of all this is when a kid performs a song, and as his classmates and teacher join in the dance, we see they’re being watched on a closed-circuit television. It’s all performances within performances.

Anderson keeps these meta-fictions spinning as an expertly choreographed and brilliantly staged nesting doll of fakery. It layers the colorful whimsy of its central story—the Star Gazers and the locals are soon trapped in town by a bizarre series of events, Close Encounters by way of Buñuel—in fictions and their tellings. It allows the movie to access both the charms of its simply plotted southwestern magical realism and its characters’ aching emotional issues, and the dizzying effort the telling. It gets at fiction itself—stories we’re told and stories we tell—and how we can get lost in it by giving ourselves over to what’s real truth within them—even kitsch, even obscure artful gestures, even when we’re unsure but “keep telling the story.” The film finds all kinds of rituals—religious sentiments, scientific methods, philosophical musings, method acting exercises, military orders, keynote addresses, backstage gossip—and notices with great melancholic empathy we’re all looking for, or clinging to, something that’ll explain our place in the vast mysteries of the universe. We need to find ourselves in the right story.

Although many of Anderson’s prior pictures allow the audience to get totally carried along in a compelling narrative and invested in characters in his controlled style, here he utilizes the grinning delights of his aesthetics of geometrical camera movements and perpendicular staging to make us always aware we’re sitting on the fourth wall. (There are even fleeting eye-contacts with the camera.) And here’s the magic: I still cared, deeply, about the characters at even the deepest levels of the fictions. There are beautiful moments of performance and writing that suddenly bring tears to the eyes with their emotional honesty. Anderson’s ability to suggest with the subtlest shifts and swiftest shimmers of interiority, whole lives behind the eyes, deep wells of regrets and confusion, longing and yearning flowers beautifully. I know I’m watching an actor playing an actor playing a character—the movie reminds us constantly—and yet, suddenly, I’m drawn in by his grief, or her confusion, or his confusion. An actress (Scarlett Johansson) in the story-within-the-story asks to run lines with a new friend and suddenly those lines (a mere half-glimpsed excerpt of another story) are somehow moving, too. It’s marvelous, the entire movie constantly making hairpin shifts between cold cerebral conceit and warm sentiment—committing fully to both and serving the thoughtfulness of each equally. The whole movie is this magic trick only a master filmmaker could pull off. It’s deeply poignant and intelligently articulated, a heady blend of heart and mind. It’s a director delivering a disquisition on his style and its intended effects, that also lands those effects with the very best of them. We’re so lucky to have Wes Anderson telling us these stories as only he can.

There's such a dearth of proper criticism these days with the 'a solid 7' brigade drowning out any other voices and the 'proper' critics pandering to the views of the knowledgeable rather than helping them understand that there's a lot more going on than meet's the uncultured eye. So thanks for this review, which does the latter.

ReplyDelete