In a filmography full of flawed father figures, there’s a good case to make for The Phoenician Scheme’s Anatole Zsa-Zsa Korda (Benicio del Toro) as the most flawed Wes Anderson father yet. He’s a rapacious international tycoon, brazenly skirting laws and regulations to exploit the world by any means necessary for his business interests. Those interests? Getting more. Little wonder his cold disregard for others leaves him dodging assassination attempts. They’re so frequent he practically yawns as he shrugs off others’ concerns about dangerous developments. “Myself, I feel very safe.” That we’ve seen an employee of his literally exploded in half in the opening moments makes us wonder where he finds that sense of safety. But it nonetheless must be this sense of mortality that drives him to invite his estranged daughter Liesl (Mia Threapleton) for a visit where he insists she leave her intention to become a nun and instead be his official heir. He takes her, and a nerdy tutor-turned-assistant (Michael Cera) on a whirlwind tour of a fictional Middle Eastern country. At each stop he renegotiates with various scoundrels and business interests (a diverse group including Tom Hanks, Riz Ahmed, Jeffrey Wright, Scarlett Johansson, Benedict Cumberbatch, and more) to fund parts of an enormous real estate and public works project that he claims will be his legacy. Of course he brings gifts to grease the wheels: complimentary hand grenades.

You may at this point have suspected that this sounds a little harsher than the usual Wes Anderson picture. Indeed, it is his coldest picture, with a hard edge and, despite his usual visual whimsical specificity, little of his obvious sentimentality. Even his masterful Grand Budapest Hotel, with its parable of encroaching fascism, found a bit more lightness in its step. Here the characters speak in the deadest of deadpan, extreme even for his style, and the emotion buried deep within is deeper still. Sure, the film is stuffed with his usual love of still-life, dioramas, old-fashioned effects, and mid-century frippery, contained in his dryly funny framing and hyper-specific structural eccentricity. (This one is built out of a series of plans kept in small, ornate boxes.) One goes to a Wes Anderson film to delight all over again at his cohesive and coherent style or one doesn’t go at all. But here in The Phoenician Scheme he’s taking a hard look at a bad man and asking what could stop the greed in his heart. All of the capitalists, con men, and crooks he meets have some stage of the same affliction. Greed is an insatiable monster. Contemplating the monster makes for a movie that’s darkly cynical, with violence tossed off as casual gags and an imperious Del Toro unflappably determined to bulldoze any obstacle in his way. In true Wes Anderson fashion, he has an intricately imagined procession of obstacles and eccentrics to reveal along that route. Is there hope for Korda? Perhaps the only thing that’ll make a bad man even a little bit better is if he could possibly be forced to have nothing at all.

Unfortunately, Korda’s in the business of more, more, more, and has a habit of corrupting all relationships toward this aim. This gives the movie an interest in the state of the soul, with religion and business and politics twisting around for purchase in materialistic persons. It’s a movie filled with schemers surrounded by paintings and literature and classical music. What beauty could a businessman possibly leave behind? Contemplating mortality, this spiritual dimension is underlined by the movie’s most startling and moving element: visions of an afterlife in blocky black-and-white where bearded sages, deceased family, and God himself sit in judgement of Korda. Whether or not his near-death experiences could help him come to a sense of self-improvement is up in the air. Like Royal Tenenbaum and Steve Zissou before him, Anatole Korda thinks he has it all figured out and needs no such self-reflection, convinced that he’s the father who knows best. But his daughter challenges him to be more of an actual, not just a theoretical, father figure, even if he may have murdered her mother. The ways in which their personalities collide and converge is a source of interest in the movie which clearly has lineage and legacy on its mind. Korda also makes mention of an unseen late father of his own whose influences on his son continue to reverberate in his decisions. (That lends poignant echoes to the short conversation which he has with God. Oh, how sons are treated.) The movie, though clever and bemused, is not as immediately lovable as Wes Anderson’s best works, so wedded as it is to its discomfiting, closed-off characters. But the ending finds Korda’s logic collapsing, and there just might be tentative hope in the wreckage.

Showing posts with label Tom Hanks. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Tom Hanks. Show all posts

Monday, July 28, 2025

Monday, November 4, 2024

Past Lives: WE LIVE IN TIME and HERE

Movies are uniquely situated to capture time. They’re built of finite moments, assembled with a definite end in mind. Unlike the open-endedness of television, the ephemerality of theater, the personalized pace of literature, or the stasis of paintings and sculptures, a movie is each moment in performance and photography and music temporally unified and held infinitely replayable. And yet to experience it in full is to move through time with its choices and for its ends. Its life-like qualities are also its greatest falseness—that we can return again to experience a life anew. It works on us by working it out through time. So when a movie leans into an idea about time, it’s meeting the medium at one of its great strengths.

This is the case with We Live in Time, which gets quite a boost by emphasizing clocks ticking and timers counting and calendars turning. It tells a pretty conventional tearful story about a couple who fall in love, have a kid, and live through illnesses. It swells with conventional sentiment. But it gets out of feeling cheap by embracing its centering of time. The story is told out of order, bouncing between high-emotion moments within the couple’s relationship. We get a wacky Meet Cute and a sober diagnosis, a wedding invitation and a pregnancy test, a career accomplishment and a medical setback. It adds to a sense of time slipping away, each discreet moment feeling so big and lasting in that moment, and yet so fleeting and short in the aggregate. The leads are played with lovely chemistry—sensual and sparkling with unforced intimacy and an easy flirtatiousness—by Florence Pugh and Andrew Garfield, who genuinely connect on screen with quiet teasing and fluttering sensitivity. They have eyes that water with unspoken fears and desires, and then run over when they’re finally spoken.

Director John Crowley (he might be best known for the lovely romantic Saoirse Ronan picture Brooklyn from about a decade ago) wisely frames the movie in warm tones and cozy close-ups, letting the performances breathe with natural interaction even as the high-gloss appearance and occasionally cliche moves tilt toward the conventional. There’s such depth of feeling to this acting duet. It adds up to quite a tear-jerking work-out, constantly teetering on the edge of melancholy even in the moments of satisfaction. It’s all those timers and tests and countdowns and waiting rooms and Save the Dates that end up important factors in so many scenes. We feel their time together slipping away. It made me acutely aware that we’re never truly cognizant of how little time we have with the ones we care about. How could we go on if we did? And how will those hundreds of little moments continue to resonate long after we’re gone?

That’s also the subject of Robert Zemeckis’ latest film: Here. In true Zemeckis fashion, it’s one of the more audacious visual experiences in recent multiplex memory. Would we expect any less from the guy who gave us Roger Rabbit’s believable hand-drawn cartoon co-stars, Forrest Gump’s proto-Deep Fakes, and three eye-boggling early motion-capture efforts? He’s been consistently pushing against the limits of popular cinema’s visual forms. This latest experiment, inspired by Richard McGuire’s graphic novel of the same name, tells the entire history of one particular spot. The camera doesn’t move. Its perspective is fixed at one angle, in one position, as everything from the dinosaurs’ extinction to the COVID pandemic plays out. It’s a simple observation, perhaps, but also a profound one, in its way, to recognize that through each and every spot on the planet the entirety of history runs. The movie draws this out by, from a flurry of images across all time, settling down into telling several stories in parallel, each with a small group of character who live here. We see: a prehistoric indigenous couple; a family in colonial America; a family in the early 20th century; a couple in the early 1940s; a family in the late-twenty-teens. Here is a home.

The film cuts freely between all of these stories, each told in chronological order, while the overall history of the place is suitably scrambled. A main storyline emerges telling the birth-to-elderly arc of one Baby Boomer (Tom Hanks) as he grows up in a childhood home that becomes his own in adulthood. He marries his high school sweetheart (Robin Wright) and then pulls a George Bailey trying to chase dreams that always lead him to stay. Life happens anyway. The cuts between the subplots and this main one tend to follow thematic threads—a man holds up his newborn so it can see the moon in one century, then another—or trace rhyming trajectories. Sometimes Zemeckis will draw a panel around one part of the frame, allowing it to stay frozen in time as the rest of the image moves, further exploiting these juxtapositions. Throughout are recurring motifs as we find the characters dealing with children, disease, technology, aging, money, work, dreaming, and despair. Same as it ever was.

The concept is so committed that I found myself tearing up at the sheer sentimental exercise of it all. (One could imagine a 60-second version repurposed for a life insurance commercial. See it and weep.) And yet the movie is also playing out at this formal distance, a tension between visual stillness and elaborate effects to age and de-age that location and its actors. Within these dense digital frames, the writing and performances are actually quite broad and theatrical, each story pretty obvious, each point triple-underlined in explicitly thematic dialogue. It’s presentational within the experimental frame. And yet I found myself so moved by its daring—crying more at the concept than the characters—that the uneven specifics’ sheer volume made up for any particular clanging miscalibration. At times Zemeckis and co-writer Eric Roth lean into their worst Gumpy tendencies, with a few scenes of cutesy cultural coincidence and a few fine ideas undone by their broadness. (Look at the scene with the grad students and wonder how those performers were possibly directed that way for the takes they used.) But the overall affect of the picture is one of visual playfulness and soft-hearted storytelling. Zemeckis is too charming a technician to take it all at face value—his roots in wacky comedies are here mixing it up with his prestige polish—and too much of a crowd-pleaser to risk letting his visual experimentation drown out the emotion. He pitches it all at such a heightened tone—even in blocking that cheats out toward the camera—that you can’t miss the overflow of human drama painted in primary colors. It’s a movie that works because of its big swings more than its small details. It just takes some time to adjust.

This is the case with We Live in Time, which gets quite a boost by emphasizing clocks ticking and timers counting and calendars turning. It tells a pretty conventional tearful story about a couple who fall in love, have a kid, and live through illnesses. It swells with conventional sentiment. But it gets out of feeling cheap by embracing its centering of time. The story is told out of order, bouncing between high-emotion moments within the couple’s relationship. We get a wacky Meet Cute and a sober diagnosis, a wedding invitation and a pregnancy test, a career accomplishment and a medical setback. It adds to a sense of time slipping away, each discreet moment feeling so big and lasting in that moment, and yet so fleeting and short in the aggregate. The leads are played with lovely chemistry—sensual and sparkling with unforced intimacy and an easy flirtatiousness—by Florence Pugh and Andrew Garfield, who genuinely connect on screen with quiet teasing and fluttering sensitivity. They have eyes that water with unspoken fears and desires, and then run over when they’re finally spoken.

Director John Crowley (he might be best known for the lovely romantic Saoirse Ronan picture Brooklyn from about a decade ago) wisely frames the movie in warm tones and cozy close-ups, letting the performances breathe with natural interaction even as the high-gloss appearance and occasionally cliche moves tilt toward the conventional. There’s such depth of feeling to this acting duet. It adds up to quite a tear-jerking work-out, constantly teetering on the edge of melancholy even in the moments of satisfaction. It’s all those timers and tests and countdowns and waiting rooms and Save the Dates that end up important factors in so many scenes. We feel their time together slipping away. It made me acutely aware that we’re never truly cognizant of how little time we have with the ones we care about. How could we go on if we did? And how will those hundreds of little moments continue to resonate long after we’re gone?

That’s also the subject of Robert Zemeckis’ latest film: Here. In true Zemeckis fashion, it’s one of the more audacious visual experiences in recent multiplex memory. Would we expect any less from the guy who gave us Roger Rabbit’s believable hand-drawn cartoon co-stars, Forrest Gump’s proto-Deep Fakes, and three eye-boggling early motion-capture efforts? He’s been consistently pushing against the limits of popular cinema’s visual forms. This latest experiment, inspired by Richard McGuire’s graphic novel of the same name, tells the entire history of one particular spot. The camera doesn’t move. Its perspective is fixed at one angle, in one position, as everything from the dinosaurs’ extinction to the COVID pandemic plays out. It’s a simple observation, perhaps, but also a profound one, in its way, to recognize that through each and every spot on the planet the entirety of history runs. The movie draws this out by, from a flurry of images across all time, settling down into telling several stories in parallel, each with a small group of character who live here. We see: a prehistoric indigenous couple; a family in colonial America; a family in the early 20th century; a couple in the early 1940s; a family in the late-twenty-teens. Here is a home.

The film cuts freely between all of these stories, each told in chronological order, while the overall history of the place is suitably scrambled. A main storyline emerges telling the birth-to-elderly arc of one Baby Boomer (Tom Hanks) as he grows up in a childhood home that becomes his own in adulthood. He marries his high school sweetheart (Robin Wright) and then pulls a George Bailey trying to chase dreams that always lead him to stay. Life happens anyway. The cuts between the subplots and this main one tend to follow thematic threads—a man holds up his newborn so it can see the moon in one century, then another—or trace rhyming trajectories. Sometimes Zemeckis will draw a panel around one part of the frame, allowing it to stay frozen in time as the rest of the image moves, further exploiting these juxtapositions. Throughout are recurring motifs as we find the characters dealing with children, disease, technology, aging, money, work, dreaming, and despair. Same as it ever was.

The concept is so committed that I found myself tearing up at the sheer sentimental exercise of it all. (One could imagine a 60-second version repurposed for a life insurance commercial. See it and weep.) And yet the movie is also playing out at this formal distance, a tension between visual stillness and elaborate effects to age and de-age that location and its actors. Within these dense digital frames, the writing and performances are actually quite broad and theatrical, each story pretty obvious, each point triple-underlined in explicitly thematic dialogue. It’s presentational within the experimental frame. And yet I found myself so moved by its daring—crying more at the concept than the characters—that the uneven specifics’ sheer volume made up for any particular clanging miscalibration. At times Zemeckis and co-writer Eric Roth lean into their worst Gumpy tendencies, with a few scenes of cutesy cultural coincidence and a few fine ideas undone by their broadness. (Look at the scene with the grad students and wonder how those performers were possibly directed that way for the takes they used.) But the overall affect of the picture is one of visual playfulness and soft-hearted storytelling. Zemeckis is too charming a technician to take it all at face value—his roots in wacky comedies are here mixing it up with his prestige polish—and too much of a crowd-pleaser to risk letting his visual experimentation drown out the emotion. He pitches it all at such a heightened tone—even in blocking that cheats out toward the camera—that you can’t miss the overflow of human drama painted in primary colors. It’s a movie that works because of its big swings more than its small details. It just takes some time to adjust.

Friday, June 23, 2023

Story Telling: ASTEROID CITY

Asteroid City is something of a skeleton key for Wes Anderson’s approach to filmmaking. It consistently tells you the whole picture is artifice all the way down—and surfaces genuine emotion on the regular anyway. That’s the Wes Anderson way. He’s always doing that—using his dollhouse designs, symmetrical blocking, picture-book precision, handcrafted effects, nesting-doll framing devices, play with aspect ratio, and deadpan witty dialogue to dig deeply into ideas and emotions that hit all the harder for having been approached slyly and indirectly. An audience can be dazzled by the parade of delights he seemingly unfolds with great whimsy, only to realize the subtleties and nuances of the earnest, deliberate intentionality behind his grand designs. Detractors who misinterpret his methods as shallow affectation or meme-worthy ticks or airless style betray only their own lack of depth.

For in a Wes Anderson movie, the apparent limits are what instead allow limitless capacity for deep contemplation. He presents us perfectly designed jewel box settings and finds his characters’ melancholies radiating, uncontainable, as they, and we, are forced to confront the messiness of art, science, family, religion, sex, violence, and everything that makes life. After his Grand Budapest Hotel found bittersweet endings in its screwball capers and romantic nostalgias cut short memorialized by a writer’s work and The French Dispatch an anthology of aesthetic reveries in a funereal tribute for a magazine editor—both pictures as political and elegiac as they are surface fizz—this new film foregrounds its form and telling even further. In so doing, it also furthers Anderson’s commitment to exploring the power of storytelling—not as a pat inspirational cliche, but as the vital stuff of human existence.

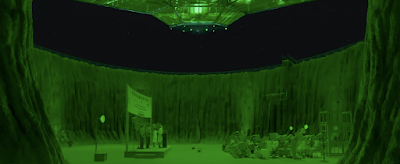

Of course a playful movie so deeply and delightfully engaged in ideas about how we explain ourselves to ourselves, and how our senses of identity and purpose are constructed, would be self-conscious as it searches for deep meaning. The movie opens on a host (Bryan Cranston) telling us we are about to watch a rehearsal for a play. In boxy black-and-white framing with theatrical lighting, we see an author (Edward Norton) at a typewriter, and the large cast assembled, and the rigging and stagehands and fakery in the wings. And then, as the story-within-that-story begins, it transforms into widescreen color full of its own artificial tricks—matte paintings, miniatures, stop-motion, and a small town where every window and door is its own proscenium arch. Here, at Asteroid City in 1955, a quaint nothing town in what’s cheerfully described as “the middle of the California, Nevada, Arizona desert,” we find a troop of Space Cadets with parents and a teacher along for a Star Gazing meetup around an ancient asteroid. The tiny motor lodge with individual cabins, next to a gas station and across from an observatory, is just another stage on which life can play out its little eccentricities.

At the center is grief, with a sad photographer father (Jason Schwartzman) telling his nerdy teen son and three cute little daughters that their mother has died. Their grandfather (Tom Hanks) is going to meet them there and drive them home, a necessity because the car just died, too. C’est la vie. It’s building a picture of a world where, no matter how much we seek to quantify and contain, people die, machines break, and the universe never loses its capacity for surprise. A mechanic (Matt Dillon) confidently tells the family that there are only two possibilities for what’s wrong with the car, only to quickly run into trouble and declare that the problem is “a third thing.” (Late in the picture, a character will matter-of-factly comment on a makeshift invention: “Everything’s connected, but nothing’s working.) More than once, a character asked “why” will respond with “It’s unclear.” And as we track back into the black-and-white world for expressionistic reenactments of the dramaturgical process, one actor will admit to not understanding his character or even the play itself. His director tells him, simply, “keep telling the story,” a phrase of advice that radiates back down into the fictions-within-fictions, and back up to us, too.

The look and tone is a fine blend of mid-century influences—Western-themed architecture and vintage technologies and designs and non-stop cowboy folk songs wafting over the town’s radios—and reflexively playful about the kinds of melodramas, both abstract and overheated, that a mid-50s writer might conjure. Knowledgeable audiences might clock the relation to the sandy sunlit widescreen staging of John Sturges’ Bad Day at Black Rock or the Technicolor small-town anxieties in Vincente Minnelli’s Some Came Running, not to mention Thornton Wilder and Samuel Beckett and Tennessee Williams and Arthur Miller and so on. (The town also has a roadrunner who chirps “meep meep,” a fine cartoon wink to foreshadow and top off the drama’s impending dusting of sci-fi elements.) And yet, for all this meta-text, we’re seeing a television special inside reenactments inside a rehearsal inside a production about a fictional town populated by dreamers and actors and schemers and scientists, every layer lost in losses and daydreams, grief and preoccupations. Perhaps an ecstatic peak of all this is when a kid performs a song, and as his classmates and teacher join in the dance, we see they’re being watched on a closed-circuit television. It’s all performances within performances.

Anderson keeps these meta-fictions spinning as an expertly choreographed and brilliantly staged nesting doll of fakery. It layers the colorful whimsy of its central story—the Star Gazers and the locals are soon trapped in town by a bizarre series of events, Close Encounters by way of Buñuel—in fictions and their tellings. It allows the movie to access both the charms of its simply plotted southwestern magical realism and its characters’ aching emotional issues, and the dizzying effort the telling. It gets at fiction itself—stories we’re told and stories we tell—and how we can get lost in it by giving ourselves over to what’s real truth within them—even kitsch, even obscure artful gestures, even when we’re unsure but “keep telling the story.” The film finds all kinds of rituals—religious sentiments, scientific methods, philosophical musings, method acting exercises, military orders, keynote addresses, backstage gossip—and notices with great melancholic empathy we’re all looking for, or clinging to, something that’ll explain our place in the vast mysteries of the universe. We need to find ourselves in the right story.

Although many of Anderson’s prior pictures allow the audience to get totally carried along in a compelling narrative and invested in characters in his controlled style, here he utilizes the grinning delights of his aesthetics of geometrical camera movements and perpendicular staging to make us always aware we’re sitting on the fourth wall. (There are even fleeting eye-contacts with the camera.) And here’s the magic: I still cared, deeply, about the characters at even the deepest levels of the fictions. There are beautiful moments of performance and writing that suddenly bring tears to the eyes with their emotional honesty. Anderson’s ability to suggest with the subtlest shifts and swiftest shimmers of interiority, whole lives behind the eyes, deep wells of regrets and confusion, longing and yearning flowers beautifully. I know I’m watching an actor playing an actor playing a character—the movie reminds us constantly—and yet, suddenly, I’m drawn in by his grief, or her confusion, or his confusion. An actress (Scarlett Johansson) in the story-within-the-story asks to run lines with a new friend and suddenly those lines (a mere half-glimpsed excerpt of another story) are somehow moving, too. It’s marvelous, the entire movie constantly making hairpin shifts between cold cerebral conceit and warm sentiment—committing fully to both and serving the thoughtfulness of each equally. The whole movie is this magic trick only a master filmmaker could pull off. It’s deeply poignant and intelligently articulated, a heady blend of heart and mind. It’s a director delivering a disquisition on his style and its intended effects, that also lands those effects with the very best of them. We’re so lucky to have Wes Anderson telling us these stories as only he can.

Sunday, June 26, 2022

If He Can Dream: ELVIS

Baz Luhrmann’s Elvis is made with an energetically heightened reality that bursts through the cliches of the rock ’n roll biopic and the overfamiliar caricature that is its subject. It restores life and vitality to both, making something enormous and earnest and enveloping. This is a perfect match of filmmaker and subject. Luhrmann has a brand of cinematic theatricality in which wall-to-wall music covers a visual feast. Every shot is a riot of movement and color, frames are filled with flashing lights and flashy design, and every performance is goaded higher and higher until most gestures are big and broad. Elvis Presley, for his part, was a shock to the system. He defined the mold that continues to mint music stars as part of a wave of midcentury entertainers who began to scramble ideas of race, sex, and gender for the mainstream. His life, too, was as outsized as his stardom. Every facet of it has passed into iconography and a cartoon of fame: his mansion, his marriage, his movies, his scandals, his eccentricities. The modern version of celebrity culture is yet another element of our world he was at the right place and time to pioneer. This movie is a huge, swaggering tour of the familiar stages of Elvis’ life and career. It goes on for nearly three hours and doesn’t dig deeper into arcane trivia or thornier contradictions. But what it does instead is recreate the sensation of the shock of the new, and the societal and showbiz tensions the shaped and destroyed him. Luhrmann’s excesses match this mood, and this project: to build a shining monument to an icon of Americana—and to see how the darkness surrounding his becoming swallowed him whole.

The result is a rock opera and historical panorama that sells the intensity and immediacy of Elvis’ impact and the titanic complicated edifice of his legacy. Shot like a diamond-studded kaleidoscope’s view, this three-hour music montage flows from one number to the next, chopped and remixed and covered and tracked, amped up, stripped down, or played straight. When it lingers on a specific performance—his first big break winning over an audience with his rhythmic wiggling on stage; a triumphant comeback with lush orchestrations and pounding crowd-pleasing stamina—it is electrifying. So often these musical biopics tell us a moment was important by assuming we’ll know it was by the recognizable hit covered by its lead. Here, Luhrmann actually makes us understand 1.) how much hard work it takes to make that sort of impact, and 2.) why his subject was a huge deal. Austin Butler plays Elvis with pretty looks and expert timing, often drenched in sweat on stage, hair flopping, legs twitching, hips plunging. We feel the exertion of putting on a show, and also can get swept up in it. All the smash-zooms in on screaming young women—partly hollering for their fresh crush, but also in surprise at the reaction they’re having—and erupting crowds in dizzying editing or split-screens doesn’t come across as parody, but genuine live-wire enthusiasm. You’d think 2007’s great poison-pen satire of the sub-genre, Walk Hard, would’ve killed these stories dead. But watching Butler come alive on screen, inhabiting the appeal of this star so fully and convincingly, one might realize it’s worth grinding through all the bad versions of these movies just to get to one this remarkable.

In Butler’s compelling performance we see anew why Elvis became who he was. He’s surrounded by Black artists as he grows up, but his whiteness gets him chances they don’t. This is partly why he courts controversy from the segregationists of the time—and one wonders how the racists right-wingers of our time won’t see themselves in the portrait of sniveling politicians complaining about how he’s exposing their white children to ideas of blackness. He’s a white man performing rhythm-and-blues, a bridge between jazz and country as he helps forge a whole new style on the backs of those who get less credit, less fame, less money. But he’s a racially ambiguous figure over the radio, and in live performance is also playing on some unspoken androgynously provocative visual appeal. He’s a hip-thrusting young man at once forceful and smooth, pulsing staccato guitar strumming with loose-limbed pleasure in his own talents, singing in a sensitive baritone timbre from soft, delicate features. (A great evocative moment finds a nasty senator’s teenagers in front of the TV, lost in desire for this new figure of lustful interest.) Subsequent rock stars would blur these lines in more overt and outré ways; but here’s a movie that restores the sexual and racial fault lines of his times in order to bolster its argument for why his stardom was such a lightning rod.

That’s the benefit of Luhrmann providing a movie that’s gloriously artificial and reverently specific as it sloshes around. He’s so good at movies that drip performative sex appeal and sexual tension, of high-gloss spectacle, loud music that resonates in the chest, expressive complicated camera moves you can hardly take in at once, and emotional dynamics you can believe in an instant. He’s also fond of tragic romantics destroyed by the troubles of their times. In his Romeo + Juliet and Moulin Rouge! and The Great Gatsby we see swooning melodrama, preening showmanship, and bombastic glamour. That’s where he loads in the opulent period style, gilded cages remixed with anachronistic fervor. And locked in the center are these tortured beautiful people who want to love and be loved. Here it’s Elvis, who searches in his family and his lovers and his audiences and, yes, even his sneaky, villainous manager (Tom Hanks) for that approval, that what he’s doing matters and will last. He’s a sensitive and artistic young man taken in, lifted up and exploited by a charismatic scheming promoter into the life of an international superstar. Hanks acts chummily threatening from within layers of makeup and a fat suit, speaking with a marble-mouthed accent and wielding a cane with a snowman top. His narration flows through the picture as well, a frustrated unreliable narrator who can’t quite prove he’s not the bad guy here. He’s a clear contrast with Elvis, the business side of the singer’s show. Somehow, they need each other, even if it will leave them worse off, too.

The movie is totally swallowed up in Elvis’ life and times. It argues that, far from being the Singular Great Man, Elvis was a product of his culture and his collaborations, forged by forces beyond his control and the contributions of others. He’s constantly surrounded by family, friends, business people, audiences, cops, politicians, and hangers-on. In the few dark, quiet moments of empty solitude—stewing in a suite, or lonely in a spotlight on an empty stage—he’s surrounded by doubt. Here’s a celebrity biopic that vigorously sells the spectacle and excitement of such a life—and the fundamental unknowability of such a man, even to himself. What a show! What a cost.

The result is a rock opera and historical panorama that sells the intensity and immediacy of Elvis’ impact and the titanic complicated edifice of his legacy. Shot like a diamond-studded kaleidoscope’s view, this three-hour music montage flows from one number to the next, chopped and remixed and covered and tracked, amped up, stripped down, or played straight. When it lingers on a specific performance—his first big break winning over an audience with his rhythmic wiggling on stage; a triumphant comeback with lush orchestrations and pounding crowd-pleasing stamina—it is electrifying. So often these musical biopics tell us a moment was important by assuming we’ll know it was by the recognizable hit covered by its lead. Here, Luhrmann actually makes us understand 1.) how much hard work it takes to make that sort of impact, and 2.) why his subject was a huge deal. Austin Butler plays Elvis with pretty looks and expert timing, often drenched in sweat on stage, hair flopping, legs twitching, hips plunging. We feel the exertion of putting on a show, and also can get swept up in it. All the smash-zooms in on screaming young women—partly hollering for their fresh crush, but also in surprise at the reaction they’re having—and erupting crowds in dizzying editing or split-screens doesn’t come across as parody, but genuine live-wire enthusiasm. You’d think 2007’s great poison-pen satire of the sub-genre, Walk Hard, would’ve killed these stories dead. But watching Butler come alive on screen, inhabiting the appeal of this star so fully and convincingly, one might realize it’s worth grinding through all the bad versions of these movies just to get to one this remarkable.

In Butler’s compelling performance we see anew why Elvis became who he was. He’s surrounded by Black artists as he grows up, but his whiteness gets him chances they don’t. This is partly why he courts controversy from the segregationists of the time—and one wonders how the racists right-wingers of our time won’t see themselves in the portrait of sniveling politicians complaining about how he’s exposing their white children to ideas of blackness. He’s a white man performing rhythm-and-blues, a bridge between jazz and country as he helps forge a whole new style on the backs of those who get less credit, less fame, less money. But he’s a racially ambiguous figure over the radio, and in live performance is also playing on some unspoken androgynously provocative visual appeal. He’s a hip-thrusting young man at once forceful and smooth, pulsing staccato guitar strumming with loose-limbed pleasure in his own talents, singing in a sensitive baritone timbre from soft, delicate features. (A great evocative moment finds a nasty senator’s teenagers in front of the TV, lost in desire for this new figure of lustful interest.) Subsequent rock stars would blur these lines in more overt and outré ways; but here’s a movie that restores the sexual and racial fault lines of his times in order to bolster its argument for why his stardom was such a lightning rod.

That’s the benefit of Luhrmann providing a movie that’s gloriously artificial and reverently specific as it sloshes around. He’s so good at movies that drip performative sex appeal and sexual tension, of high-gloss spectacle, loud music that resonates in the chest, expressive complicated camera moves you can hardly take in at once, and emotional dynamics you can believe in an instant. He’s also fond of tragic romantics destroyed by the troubles of their times. In his Romeo + Juliet and Moulin Rouge! and The Great Gatsby we see swooning melodrama, preening showmanship, and bombastic glamour. That’s where he loads in the opulent period style, gilded cages remixed with anachronistic fervor. And locked in the center are these tortured beautiful people who want to love and be loved. Here it’s Elvis, who searches in his family and his lovers and his audiences and, yes, even his sneaky, villainous manager (Tom Hanks) for that approval, that what he’s doing matters and will last. He’s a sensitive and artistic young man taken in, lifted up and exploited by a charismatic scheming promoter into the life of an international superstar. Hanks acts chummily threatening from within layers of makeup and a fat suit, speaking with a marble-mouthed accent and wielding a cane with a snowman top. His narration flows through the picture as well, a frustrated unreliable narrator who can’t quite prove he’s not the bad guy here. He’s a clear contrast with Elvis, the business side of the singer’s show. Somehow, they need each other, even if it will leave them worse off, too.

The movie is totally swallowed up in Elvis’ life and times. It argues that, far from being the Singular Great Man, Elvis was a product of his culture and his collaborations, forged by forces beyond his control and the contributions of others. He’s constantly surrounded by family, friends, business people, audiences, cops, politicians, and hangers-on. In the few dark, quiet moments of empty solitude—stewing in a suite, or lonely in a spotlight on an empty stage—he’s surrounded by doubt. Here’s a celebrity biopic that vigorously sells the spectacle and excitement of such a life—and the fundamental unknowability of such a man, even to himself. What a show! What a cost.

Labels:

Austin Butler,

Baz Luhrmann,

Tom Hanks

No comments:

Sunday, July 12, 2020

Captain's Orders: GREYHOUND

With Greyhound, Tom Hanks has written a film perfectly fitted to his Movie Star persona. Like in his great recent films Sully and Captain Phillips, he’s playing a model of good leadership, built sturdily upon moral virtue, human and humane in the face of unbearable danger and terrible odds. This World War II thriller casts him in the role of a career Navy man captaining his first ship. The mission is to escort a convoy of supply ships from America to England. As the film begins, they’ve lost their air support from the States. It will be a few dark and stormy days until they meet up with the English planes that will take its place. During this time, they will be hunted by a pack of German U-boats, intent on picking off the convoy one by one, sowing confusion and wearing down their resources until they can move in for the kill. The enemy, heard only in ominous taunting radio transmissions, overtly declare themselves wolfish predators, but the sturdy filmmaking, from director Aaron Schneider (Get Low), makes them just as much shark-like, surfacing as if with a fin, circling like Jaws. Strategic aerial shots emphasize the game of cat-and-mouse on display, a bit of literal Battleship maneuvering. They’re on the open ocean, but the film is mostly claustrophobic. Close-quarters close-ups and medium shots in cramped situations have the men (from Hanks to second-in-command Stephen Graham and a host of young character actors) pressed against the bulkheads, straining against the waves, manning their battle stations.

The tension never slacks. It’s a barrage of snappy jargon and terse commands, every gesture and decision drawn with verisimilitude and effective B-movie snap. Based on a novel by Horatio Hornblower author, and WWII vet, C.S. Forester, it feels like it gets every detail right. The radar pings. The water crashes. The rudder shudders. Hanks commands the film with his quiet steady hand, a good man who feels the weight of responsibility, each life resting heavily on his shoulder, each mistake settling uneasily on his soul. His screenplay is a model of efficiency, starting as the mission crosses into its most dangerous passage, with only an exceedingly brief early flashback to humanize his character’s home life. It proceeds full steam ahead into an elegantly simple 80-minute suspense sequence. The clean, crisp frames and pulse-raising ticking clock make the slowly diminishing hours to rescue pass with the adrenaline of stalking enemies, exciting strategy, and painful losses. It’s an effective thriller, not because the whole war or a decisive battle is at stake, but because these particular boats, and the souls on them, matter. Because they’re full of people, and their captain cares, and every wasted round, every wasted second, is one precarious step away from their goal, we care. Every ounce of sentimentality, of relief, is hard-fought, and well-earned.

The tension never slacks. It’s a barrage of snappy jargon and terse commands, every gesture and decision drawn with verisimilitude and effective B-movie snap. Based on a novel by Horatio Hornblower author, and WWII vet, C.S. Forester, it feels like it gets every detail right. The radar pings. The water crashes. The rudder shudders. Hanks commands the film with his quiet steady hand, a good man who feels the weight of responsibility, each life resting heavily on his shoulder, each mistake settling uneasily on his soul. His screenplay is a model of efficiency, starting as the mission crosses into its most dangerous passage, with only an exceedingly brief early flashback to humanize his character’s home life. It proceeds full steam ahead into an elegantly simple 80-minute suspense sequence. The clean, crisp frames and pulse-raising ticking clock make the slowly diminishing hours to rescue pass with the adrenaline of stalking enemies, exciting strategy, and painful losses. It’s an effective thriller, not because the whole war or a decisive battle is at stake, but because these particular boats, and the souls on them, matter. Because they’re full of people, and their captain cares, and every wasted round, every wasted second, is one precarious step away from their goal, we care. Every ounce of sentimentality, of relief, is hard-fought, and well-earned.

Labels:

Aaron Schneider,

Stephen Graham,

Tom Hanks

No comments:

Sunday, October 30, 2016

Bored to Death: INFERNO

There are worse movies than Inferno, movies so inept, confused, ill-considered, or offensive

they’re impossible to defend let alone sit through. But that makes it all the

more depressing to realize Inferno is

the only thing a movie can be that’s worse than bad. It is boring. I don’t mean

to say it is slow or off-putting or strange or lazy. No, it is just deafeningly

empty from the first frame to the last, completely devoid of interest or

entertainment. If it was a bad movie it could at least kick up ludicrous

silliness or something so mind-bogglingly tone deaf it’d be worth unpacking.

Here we simply have a movie with no real reason to exist, incapable of making

an argument for itself. It merely is, playing out with all the excitement and

urgency of a talented group of Hollywood craftspeople signing off on a

contractual obligation. It’s the kind of movie so tediously uninteresting you

wonder if it was possible everyone was sleepwalking behind the scenes, or maybe

trading sightseeing tips for their European downtime on Sony’s dime.

Clearly a commercial commitment, Sony couldn’t indefinitely

sit on the rights to Dan Brown’s successful books about Harvard symbologist

Robert Langdon, not after director Ron Howard and star Tom Hanks turned them

into two good-sized hits already. The Da

Vinci Code (2006) and Angels &

Demons (2009) were not great thrillers, but at least they had their pulpy

fun pretending their plot mechanics were wrapped in learning, with history

lectures and Catholic conspiracy. Any movies that can feature both lengthy art

appreciation monologues and Paul Bettany as a self-flagellating albino monk (in

the first) or Ewan McGregor as a Cardinal parachuting out of an exploding

helicopter (in the second) can’t be all bad. These were fairly self-serious works,

B-movies impressed by their own footnotes and inflated with big budgets and big

stars. Still, nothing prepared me for how exhausted and joyless Inferno was. Compared to this new film,

its predecessors are models of humble, slight, and economical filmmaking. This

one stumbles through an endless bleary plot without a single second of rooting

interest, believable stakes, or photographic interest.

It starts with Langdon (Hanks) waking up in a Florence

hospital suffering amnesia from a head wound. His doctor (Felicity Jones) tells

him he was attacked. Confused and suffering hallucinogenic flashes of horror imagery

– the movie takes glum grotesqueries as humdrum – Langdon flees with his

caretaker after a policewoman opens fire on them. Now he must remember why he’s

now wrapped up in a globetrotting art-adjacent adventure, racing to prevent an

apocalyptic event. Because he’s done sort of thing twice before he’s well

equipped to get up to speed as he fumbles around the scrambled passages of his

mind. Maybe it has something to do with the visual representation of Dante’s

Inferno he finds in his pocket, and which has been altered to include clues to

a hidden cache of plague virus that would wipe out 95% of the world’s

population if unleashed. You can see why the World Health Organization, which

this movie imagines operates as an international SWAT team, is hot on their

trail. The mystery is why they think Langdon has something to do with it.

I can forgive many an incredulously strained plot, but see

if you can follow this. Say you were a brilliant but eccentric sociopathic

billionaire scientist with a goal of reversing the world’s overpopulation with

your custom-made plague. You’ve hidden it in a bag that’ll blow up on a certain

day and time. Would you: A.) tell no one, sit back quietly, and let it do its

thing; or B.) throw yourself off a building, leaving behind an elaborate set of

art-history scavenger hunt clues leading to your biological weapon of mass

destruction? I get when Langdon is investigating a conspiracy with historical

roots why sussing out clues in paintings and monuments is a helpful strategy,

but why would Inferno’s villain (Ben

Foster) create new clues on old art? If he was really intent on kickstarting

the apocalypse, why leave room for a professor to figure it out and stop you?

There’s little motivation behind anyone’s behavior in this movie, including WHO

agents (Sidse Babett Knudsen and Omar Sy) and a mysterious fixer whose office

is aboard a freighter in the Adriatic (Irrfan Khan). They change sides a couple

times each for seemingly no reason other than cheap surprise.

Inferno is a movie

that’ll test a lot of assumptions. Think between Ron Howard directing and David

Koepp writing they could surely cobble together a half-interesting story? Think

national treasure Tom Hanks could reliably deploy his star power? Think a

supporting cast of fine actors could bring something to the table? Think some

solid, reliable Hollywood craft – cinematography from occasional Howard

collaborator Salvatore Totino, score from the busy Hans Zimmer – could at least

render a movie watchable? Prepare to be disappointed. It’s an entire movie of

people going through the motions. It can’t even make stunning locales in

Florence, Venice, and Istanbul look like the good museum-hopping travelogue

thriller it could’ve been. The movie is cramped and ugly – maybe the better to

emphasize its villain’s complaint about too many people? – and the way the plot

unfolds around an amnesiac hero is treated for mere confusion. This only serves

to hobble what should be a swaggering Hanks by making him squint and stagger

while reading clues to the other characters, dragged along by the boring plot

without clear drive or goals of his own. He can’t remember why he’s there or

why he should care, and I could relate. The only reason to see this movie is if

you want a dark room in which you could nap for a couple hours.

Friday, September 9, 2016

Fly Hard: SULLY

A most unusually structured mainstream Hollywood effort,

Clint Eastwood’s Sully is more than

you’d expect from a based-on-a-true-miracle movie. It has the requisite

stunningly realized and vividly recreated central reenactment of an amazing

real-life event, in this case Captain Sully’s emergency water landing of a US Airways

jet in New York City’s Hudson River on January 15, 2009. But Eastwood’s film

isn’t interested in easy heroism. It’s about process, about skilled people

doing their jobs to the best of their abilities and about the constant churning

reliving of a traumatic event in its swirling aftermath. This is a movie that

knows just because the outcome was a success – the reason the story is so

memorable in the first place is not simply that a jet went down, but that every

single passenger and crew member lived – doesn’t make the event any less

rattling. And just because we know the outcome doesn’t make it any less

harrowing.

The movie knows we know what happened and doesn’t take any

steps to hide it. Todd Komarnicki’s screenplay begins in a nightmare, as Sully

(Tom Hanks) awakes the morning after the miracle having dreamt it had gone

wrong and they all went down in flames. A news report is hammering away with

the real ending: all survived. This is a movie about what happened that day,

told from a variety of angles, remembrances, and reenactments. Eventually the

movie arrives at its centerpiece: a lengthy, involving, grippingly

detail-oriented view of the event from boarding to takeoff to sudden bird strikes

mere moments later that leave both engines useless and then a long, scary

descent past the city and into the river. But first we see Sully and his

co-pilot (Aaron Eckhart) interviewed by the National Transportation Safety

Board (whose members include Mike O’Malley and Anna Gunn). They’re forced to tell

their story, explain why they couldn’t make it safely back to a runway. This is

a movie not about bold men taking decisive heroic action. It’s about instinct,

knowledge, training, and group efforts. It’s about doing the job.

Circling the main event, Sully’s

present tense follows the man recovering. We see the crash in dream, flashback,

news coverage, interviews, interrogations, flight recordings, and simulations.

It’s a sturdy evocation of a man whose mind continually, inevitably returns

again and again to relive his trauma by personal choice and public need. He’s

still in shock, stuck in a hotel waiting for the board’s investigation to

complete so he can get back in the air. Meanwhile, strangers awed by his

noteworthy feat stop to shake his hand or give him a hug, Katie Couric and

David Letterman want him on their shows, and his wife (Laura Linney) calls to

check up on him. But none of this interrupts his mind as he wonders if he did

all he could. Did he make the right decisions? Could this have all been

avoided? The answer is yes and no. He behaved perfectly under pressure, and

accidents happen. But his work ethic is such that he simply can’t square the

heroic image in public with his humble workaday private self. He’s just one

man, who happened to have the right training and the right experience to allow

him to make the right calls quickly and under pressure. He just wanted to make

sure everyone was safe.

Eastwood lingers on this ordinary professionalism, using

Hanks’ subtle humility and aw-shucks low-key Americana persona to great effect.

Hanks projects a confident, compassionate, fatherly presence. It’s a strong,

honest, hardworking masculinity that’s not bravado, but simply routine and

behavioral. He’s warm and earnest, but not arrogant or aggressive. He’s simply

nice. It’s a perfect part of the film’s portrait of process that reveals the

everyday bravery of people who have skills, knowledge, expertise, empathy, and

a moral sense of duty. (And like Eastwood’s other recent films – J. Edgar, Jersey Boys, American Sniper

– it’s interested in the effects public feats have on private lives.) Sully is a movie that finds different

perspectives beyond the leading man: the steady co-pilot, the efficient flight

attendants, the alert traffic controller, the responsive passengers, the

confident coast guard and quick-thinking ferry boat captains who race to the

scene. Everyone plays an important part and living through it marks all. A

Hawksian vision of humanity at its best and most cooperative, it’s a quietly

moving movie about people in peril not succumbing to selfish panic, but taking

one step at a time to safety. The film is understated, humane, warm, even

softly funny, recognizing the normality of the men and women who experienced

something that doesn’t normally succeed. The lead of the investigation

eventually admits it’s the first time he’s listened to a black box while

sitting next to the pilots.

Shot in bright and crisp digital full-frame IMAX by

cinematographer Tom Stern, the movie’s most overwhelming when it puts the

audience in the plane as it dives – at once terrifyingly fast and agonizingly

slow – to the river. Eastwood increases the panic by tracing the plane’s arc

past skyscrapers and skyline, even coming close to a bridge. The words 9/11 are

never spoken in the film, but hang over the proceedings, never more so than in

a moving passage during the centerpiece sequence that cuts to New Yorkers

catching sight of the low-flying jet, the horror and surprise registering on

their faces with a clear “oh, no, not again” feeling. It’s done largely

silently, adding to the haunting reminder of how badly this could have ended. As

the movie continues in its repetitions, finding new viewpoints from and techniques

through which to view and explain the miracle, Eastwood lets the details

accrue. Though it opens by reminding us of the outcome and then lets us see the

events in so many ways so many times, it retains its suspense and its

fascination the whole way through. It has the skill to show us an amazing feat,

and the perspective to know the outcome was astounding through nothing more

than capable people committed to doing the best they could with the

circumstances given to them.

Thursday, December 12, 2013

Spoonfuls of Sugar: SAVING MR. BANKS

It’s no secret that Walt Disney Pictures has been creatively

floundering as of late. The past decade saw their animation studio take a

confused tumble after the heights of their 90’s renaissance while their live

action filmmaking got only the rare hit (Pirates

of the Caribbean) between failures both instantly forgettable (G-Force, College Road Trip, Prince of Persia)

and unfairly maligned (the fun John

Carter and misunderstood Lone Ranger).

Despite their considerable charms, Tangled

and Frozen alone do not a new

golden age make. No wonder they want to cast their corporate eye backwards with

Saving Mr. Banks, remembering a high

point of creative and commercial success through rosy glasses and the glossiest

of Hollywood polish. The movie considers the early 1960s, in particular the

preliminary stages of the making of 1964’s Mary

Poppins, not-so-coincidentally out now in a sparkling new transfer on

Blu-ray. Banks twinkles through

script notes, songwriting, and storyboard meetings, largely focusing on Walt

Disney’s attempts to convince P.L. Travers, the author of the Poppins books, to sign over the rights.

Travers was notoriously reluctant to turn her beloved

writing over to the hands of Hollywood in general and Disney in particular. The

movie casts the generally likable Emma Thompson in the role. Her performance

creates a woman walking through life in brisk and brittle judgment, but with

the inevitable softening always just under the surface of her snapping. In the

film’s opening, she has to be talked into flying to Los Angeles to take a

meeting with Disney. We hear that her royalties are drying up and so could use

the boost of income. That the sign of her financial troubles is her having

recently fired her assistant is not necessarily the most sympathetic of

hardships is no matter. The movie isn’t about her financial pressures giving

her reason to sign the contract. It’s about how a controlling creative type

meets another controlling creative type and learns to compromise for the good

of creating a classic film.

For this is a movie aware at all times that Mary Poppins will become an all-time

classic. When Mr. Disney (Tom Hanks, so well-liked on his own, all he has to do

is show up in costume to communicate some of Disney’s showbiz charm) has

Travers sit in on development meetings with co-writer Don DaGradi (Bradley

Whitford), it’s clear that every decision the studio makes that we can

recognize from Poppins is meant to be

the correct decision. When Travers snaps at the songwriting Sherman brothers

(B.J. Novak and Jason Schwartzman) over a small made-up word in one of the

opening lyrics, they awkwardly glance at their pages of music, the camera

dutifully focusing in on the word “Supercalifragilisticexpialidocious” as

punchline. Saving Mr. Banks plays

upon our knowledge for one of the studio’s crowning achievements – one of the

company’s very best films and their best live action effort by a country mile.

Poppins is a movie

of such pure delight that it can’t help but rub off on this one a little bit.

Filled up with Poppins’ songs and

winking references to specific lines and images, Banks and its charming cast carries a residual charge. So what if director

John Lee Hancock (of The Rookie, The Alamo, and The Blind Side) shoots the film with very little cinematic

inspiration of his own, dutifully shooting the script glossily and anonymously.

All the better for Poppins movie

magic to shine through. The script by Kelly Marcel and Sue Smith very nearly

makes Travers into a simple killjoy. Sure, she taps her toes to “Let’s Go Fly a

Kite,” but she threatens to cancel the whole project after learning the dancing

penguins will be cartoons and not trained penguins. There’s sympathy to be

found in her position – after all, Disney is playing a game of semantics

telling her the movie will not be animated, and then eventually admitting “not

animated” doesn’t necessarily mean “no animation.”

Travers was so against the frivolity and sugar of Disney,

especially when it came to adapting her books, that one imagines having her

life turned into a Disney movie could be a posthumous indignity. If she fought

so hard to preserve the most important details of her books, imagine what she’d

have to say about this movie. It’s a case of history written by the winners, a

true story about a woman who feared the company would take a good story, sand

off the hard edges, and make it into simpleton schmaltz. And yet Saving Mr. Banks, for all its borrowed charms in the occasionally

repetitive showbiz scenes, works. The screenplay weaves in flashbacks of

biographical detail, finding Travers as a young girl (Annie Rose Buckley) in

the Australian outback with her depressed mother (Ruth Wilson) and alcoholic

banker father (Colin Farrell). These scenes have the emotional charge the fizzy

Hollywood storyline doesn’t, and when the film finds sequences in which the

flashback past and filmmaking present collide, it’s surprisingly moving. Though

a rough correlation between her story and her life is too mushy to work as

literary analysis, it makes for fine sentimental cinema.

The film is ultimately about a peculiar paradox that can

befall creative types. Travers and Disney are both so committed to their own

visions for the project, they do not see the value in anything that varies from

what’s already in their heads. They’re stuck talking past each other, unable to

use their considerable creativities to compromise. This is an interesting

conflict on which to hang a story, especially considering that there’s no

reconciliation here. It’s a strange tone for a film to settle upon, on the one

hand polishing its corporate reputation while still finding some degree of

sympathy for the woman who felt so compromised by Disney. Travers simply

softens enough to sign away and Poppins

is made more or less as Disney decided. That in real life, she refused to sign

over the sequel rights after seeing the film is perhaps indicative this new

film concludes slightly sweeter than it should. In the end, I reacted to Saving Mr. Banks in much the same way it

portrays Travers at the premiere of Poppins.

What it does, it does well. What she finds disagreeable leaves her arms crossed

with a face of stone. What she finds it gets absolutely right moves her.

Monday, October 14, 2013

Just Business: CAPTAIN PHILLIPS

Exhausting and exhaustive, Captain Phillips is a process-oriented film of unrelenting tension.

Detailing the true story of how, in 2009, a band of Somali pirates managed to

board an American freighter in international waters off the coast of Africa and

ended up holding the ship’s captain hostage for four days, the film’s approach

finds the distance between us and them drawing small. The opening scenes are

all about world economics, with two groups of men setting sail with very

different, but ultimately convergent, goals. The freighter is loaded with cargo

while Captain Phillips (Tom Hanks) makes last minute checks, running down the

corporate checklist. In a village in Somalia, a band of pirates are spurred to

action by the local warlord, gathering boats and crew to go hunting for

vulnerable targets in the ocean beyond their shores. They’re all in it for the

money.

In the opening scene, the theme of global economic forces is

made all too clear as clunky thematic exposition is spoken between Phillips and

his wife (Catherine Keener). The world is changed, he says, wheels are moving,

forces beyond their control. By the time the captain of the pirates (Barkhad

Abdi) comes face to face with Phillips, he tells him their piracy is “only

business.” Late in the film, he explains his boss will expect money when they

return. “We’ve all got bosses,” Phillips replies. The film splits cleanly in

two, the opening an extended setup that brings the freighter and the pirates

into contact and crisis, leaving the second half dedicated to cutting between

the military rescue operation and the increasingly claustrophobic and desperate

events on board as a heist becomes a hostage situation. It largely shifts

thematic gesturing to off-hand remarks, driving forward with ticking

reportorial momentum.

The film reflects its preoccupations with process and

business in its simplicity. A tense reenactment of a story that was all over

the news in recent memory, there’s a factual frisson to the way the film

unfolds. The screenplay by Billy Ray is, a clunky first scene aside, relatively

restricted to jargon, strategy, and jostling for power and advantage in an

increasingly difficult scenario for all involved. Though it could easily become

an overpowering triumphalist picture, with one of the most likeable movie stars

on the planet terrorized by third-world criminals and eventually rescued by the

firepower of the United States, there is a remarkably balanced approach that

finds the terror of the situation in how inescapable it becomes. Everyone is

simply doing the job they’ve been given, responding to variables according to

the best of their professional knowledge and abilities.

Hanks does strong, nuanced work here as a man with a

professional imperative to keep his cool to save his crew and cargo, as well as

an inner strength, his will to survive driving him to keep all parties from

becoming irreparably inflamed. He’s not a hero, merely a smart, capable man who

keeps a level head. The final stretch of the film, when he’s pushed past the

breaking point and enters a state of shock, is some of the rawest acting Hanks

has done in years. Abdi, as the leader of Phillips’s Somali captors, is clearly

orchestrating a criminal and inexcusable act, but his performance captures

shades of doubt and pride that prevent his characterization from becoming

abstract villainy. He’s a desperate man in desperate circumstances, finding it

hard to control a situation he thought would be easy ransom as it spirals out

of control and it becomes clearer that it’ll be hard to make it out. It’s

almost sad when, late in the film when it’s clear to all involved he and his

men will more likely be captured or killed than receive riches, he’s asked why

he continues to hold Captain Phillips hostage and replies that he’s come too

far to turn back.

Directed by Paul Greengrass, the film jitters with his

trademark shaky-cam verisimilitude. With exceptional action films The Bourne Supremacy and The Bourne Ultimatum, he helped set the

standard for chaos cinema, painting action as scrambling sequences of elaborate

franticness, pushing blockbuster cinema towards a standard of abstract

adrenaline that few filmmakers could match. Many would borrow the techniques,

but few could copy the effects. His you-are-there docu-thriller immediacy did

claustrophobic wonders for his dread-filled United

93, a real-life disaster picture that valorizes the passengers who died

diverting a hijacked airliner on September 11, 2001. In Captain Phillips, Greengrass brings a similar sense of weight and

tension, a sense of enclosure of space and situation, cinematographer Barry Ackroyd's widescreen framing refusing

to open up. Even wide shots of ships at sea feel trapped, the weight of the suspense

crushing down even there.

The film uses its sensations to simply recreate a recent

event and it’s admirable how even-handed it manages to be. Even better, how the

film refuses to give easy relief. The final minutes are extraordinary. The

saving gunshots come fast, leaving the scene bloody and resolutely resisting

celebration. Hanks’ final scene is not one of calm, but one of safety slowly

quaking its way into a body still shaking with unbelievable stress. Greengrass

leaves us with scenes much like those we’ve been watching the entire runtime,

professionals simply doing what must be done. Tension may be released from this

particular narrative, but the world goes on just as before.

Monday, October 29, 2012

What is Any Ocean but a Multitude of Drops? CLOUD ATLAS

Starting with nothing less than a Homeric incantation in

which a white-haired old man stares into a crackling fire and seems to summon

the fiction into being, Cloud Atlas, an ambitious adaptation of David

Mitchell’s tricky novel, is the kind of movie that’s easy to recommend and

admire, if for no other reason than that nothing quite like it has ever existed

and is unlikely to come around again any time soon. It wobbles at times, but luckily

it’s ultimately better than the sum of its gimmicks. This is a complicated film

about simple truths: love, ambition, knowledge, power. A major motif is a

musical composition that one of the characters writes called “The Cloud Atlas

Sextet.” It’s a lush, haunting piece of music that winds its way through the

soundtrack and, by its very nature, echoes the major structural conceit of the

film. A sextet is a piece of music to be played by six musicians. This film –

like the novel before it – contains six stories, any one of which could easily

expand into its own film, but together combine into one gorgeous whole.

Spanning centuries and genres, the film breaks apart the

book’s chronological and mirrored presentation and instead places the six

stories parallel to each other, cutting between the stories with a gleeful, witty,

dexterous montage that recalls D.W. Griffith’s 1916 feature Intolerance in the way it so skillfully

weaves in and out of varying plotlines. A massive undertaking, three directors,

Tom Tykwer (of Run Lola Run and Perfume: The Story of a Murderer) and

Lana and Andy Wachowski (of The Matrix

films and Speed Racer) split the six

sections among them, adapting and directing separately but from a shared common

vision so that the story flows both stylistically and emotionally. Like some

strange geometric object with many sides and layers, the film grows all the

more epic by expanding outwards through time and space.

It takes us to the Pacific Ocean in the nineteenth century

aboard a ship sailing towards America. Then, we’re in Europe in the 1930s, following

a disinherited, but ambitious and talented, music student to the home of an

elderly composer. Next, we’re in 1970s America, following an intrepid reporter

into a conspiracy at a new nuclear power plant. On to the present, where we

find a publisher who is the victim of a mean brotherly prank and stuck in an

unexpected place. Then we’re to the future, where a clone slave describes her

story of finding awareness of the consumerist dystopia she lives in. Finally,

to the far future, where we find a post-apocalyptic world that has returned to

clannish living in the wilderness, where the peaceful people are terrorized by

a tribe of aggressive cannibals. Tykwer and the Wachowskis present each setting

with handsomely realized production design and detailed special effects. Moving

between them is anything but disorienting; it’s, more often than not,

invigorating.

Almost too much to handle in one sitting, this film is a

rush of character and incident, themes and patterns, echoes upon echoes, all

distinctive melodies that fade and reoccur time and again. Some sequences play

more successfully than others, but the film is largely fascinating and

generally gripping as it becomes a symphony of imagery and genre, returning

again and again to mistakes humankind makes, the benefits and constraints of

orderly society, and the way underdogs try to find the right thing to do

against all odds. The themes play out repeatedly in a flurry of glancingly interconnected

genre variations. What appears as drama later plays as comedy, as action, as

mystery, as tragedy. Tykwer and the Wachowskis have put the film together in

such a way that the editing escalates with the intensity of each plotline,

bouncing in an echoing flurry during rhyming plot points (escapes, reversals of

fortune, setbacks, reunions) and settling down for more languid idylls when the

plots simply simmer along. By turns thrilling, romantic, disturbing,

suspenseful, and sexy, there’s a fluidity here that makes this a breathless three-hour

experience. The film moves smoothly and sharply between six richly imagined

stories that connect more spiritually and metaphysically than they do

literally, and yet artifacts of one story may appear in another, sets may be

redressed for maximum déjà vu, characters in one story may dream glimpses of

another. This isn’t a puzzle to be solved, but rather a stylish assertion that

people are inescapably connected to their circumstances and to those who lived

before and will live after.

In order to underline its insistence upon the connectedness

of mankind then, now, and always, the film features the same cast in each

story, making it possible to get a sense of the progression of a soul through

time, each reincarnation living up (or down) to the example of earlier

experiences and choices. Through mostly convincing makeup, actors cross all

manner of conventions, playing not just against type, but crossing race, gender,

age, and sexual orientation in unexpected ways. (Some of the biggest pleasant

surprises in the film are in the end credits, so I’ll attempt to preserve them.)

For example, Tom Hanks appears as a crackpot doctor, then again as a thuggish

wannabe writer, then again as a haunted future tribesman, among other roles.

This is a large, talented and eclectic cast with Halle Berry, Jim Broadbent,

Hugo Weaving, Keith David, Doona Bae, Jim Sturgess, Ben Whishaw, James D’Arcy, David

Gyasi, Susan Sarandon and Hugh Grant delivering strong performances, appearing

over and over, sometimes obviously, sometimes unrecognizably or for only a

moment. This allows the filmmakers to dovetail the storylines even further, for

what is denied in one (lovers torn apart, say) may be given back in the space

of an edit (lovers, not the same people, but played by the same performers,

reunited).

Though some will undoubtedly be turned away by its earnest

(if vague) spirituality and messy philosophical bombast, this is the kind of

film that, if you let it, opens up an endless spiral of deep thoughts. You

could think it over and spin theories about what it all means for hours. To me,

that’s part of the fun. It’s a historical drama, a romance, a mystery, a sci-fi

epic, a comedy, and a post-apocalyptic fantasy all at once. In placing them all

in the same film and running them concurrently Tykwer and the Wachowskis have

created a moving and exciting epic that seems to circle human nature as each

iteration finds characters struggling against societal conventions to do the

right thing. The powerful scheme and rationalize ways to stay on top; those

below them yearn for greater freedom and greater meaning. There’s much talk

about connection and kindred spirits; at one point a character idly wonders why

“we keep making the same mistakes…” It accumulates more than it coheres, and

yet that’s the bold, beautiful mystery of Cloud

Atlas, that it invites a viewer into a swirl of imagery, genre, and

character, to be dazzled by virtuosic acting and effective filmmaking, to get

lost amongst the connections and coincidences, to enjoy and perhaps be moved by

the shapes and patterns formed by souls drifting through time and space.

Wednesday, March 28, 2012

Too Soon: EXTREMELY LOUD & INCREDIBLY CLOSE

I had Extremely Loud

& Incredibly Close on my list of films to see before I finalized my top

ten list for 2011, but after the waves of critical negativity greeted its

limited release, I took it off the list. The trailer, which for some reason

seemed to play before at least a half-dozen films I saw during the fall, hadn’t

been promising. But the pedigree (based on a Jonathan Safran Foer novel of some

note, starring a bunch of Oscar winners and nominees that I quite like,

directed by thrice-nominated Stephen Daldry) still had me interested. I had

marked it down as a low priority and was all ready to move on when the Oscar

nominations were announced. Surely the big surprise of that morning, the film

made it on the list of nine nominees for Best Picture. Having seen the other

eight titles, I once again felt the begrudging need to head out to the theater

and see for myself.

I caught it in a mall multiplex near the end of its

theatrical run. I’m glad I did. The film is not without it’s flaws. That’s

putting it mildly. But I found it to be a compelling and even moving

experience. Is it mechanical and manipulative in its use of a recent tragedy to

give weight to its otherwise flimsy story? Certainly. But it barreled past my

objections and worked on me. I can’t deny that it’s heavy handed, that it might

just be too slick for its own good, that it meanders and sometimes bobbles its

tone. But it’s also often powerfully acted and quietly absorbing in ways that

surprised me given all the noxious critical reactions that surrounded its

release.

The film is about a young boy (Thomas Horn) whose father

(Tom Hanks) had a meeting in the World Trade Center on September 11, 2001. In

the opening scene he expresses disgust that his mother (Sandra Bullock) decided,

since no body was recovered, to bury an empty coffin. His father’s death seems

to resist closure. It is a wound that won’t heal, a scab at which he keeps picking

away, hiding a makeshift shrine to 9/11 in the uppermost corner of his bedroom

closet. For him, the idea of closure is at once intensely necessary and to be

resisted. There can be no closure. The most wounding moment of the film comes

in a scene that’s the least heavy-handed and the best acted in which the boy

finds just the right words to hurt his mother, to lash out at the only person

who can share his pain. In that scene, Horn is capably upset and Bullock's reaction is

devastating. It’s a moment of emotional impact that I wouldn’t want to shrug

off lightly.

Before 9/11, the father would create scavenger hunts to help

the shy, awkward, but intelligent child learn how to go out into the world and

find his way around obstacles. In his father’s death, the son finds the biggest