Writer-director Jordan Peele’s latest feature, Nope, starts with a scary bit of monkey business. The taping of a fictional 90’s sitcom co-starring a chimpanzee is violently interrupted by the sudden snapping of said animal costar. We see, mostly hidden behind the set’s blood-splattered sofa, the unmoving legs of a presumably mortally wounded cast member. The chimp sits, almost bewildered at its own actions, nudging the unmoving body. Then it turns and looks straight down the lens, as if seeing us, the audience, aware of our presence observing this awful spectacle. Wait, you might think at this point, isn’t this a movie advertised with the promise of a UFO? This chimp is, indeed, narratively superfluous to that core idea, but is also a key to the whole thing. This unsettling moment, brought back in a longer flashback late in the picture, has a connection to the backstory of a minor supporting character. But it’s also priming us to see this as a movie about people’s attempts to control the uncontrollable, in doomed attempts to capture the wilds of nature by taming it within the images we are used to.

As great as Peele’s previous pictures are—and Get Out and Us are certainly deserving of their critical hosannas and box office appeal—they do love plainly presenting, even openly declaiming, their allegorical intents. A thrill of Nope is its wide open spaces in look and story—big blue skies against a western backdrop, and plot and character and theme left with evocative implications. It’s a film of images about images. It’s rich in negative space, literal and figurative, it can fill in with sublime suspense and awe, and room to plant ideas and connections and deepening understandings to grow in the viewers’ minds. It’s a movie, then, about the futility of bringing the unimaginable down to earth through our capacity to document it. Peele is confident enough in his filmmaking, his concept, and his cast to let scenes play out with relaxed rhythms that slowly constrict into pinpoint tension, and for ideas to slowly amble until they’re suddenly crystal clear. It’s evident Peele is solidly one of those filmmakers with such a sure hand that, no matter where he takes us, we can trust he’ll make it worth our while.

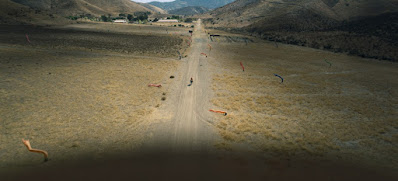

The film’s grounding in the interplay between the moving image and lived experience is immediately apparent. Set on a ranch in rural California, it follows siblings (Daniel Kaluuya and Keke Palmer) who’ve just inherited the property after the death of their Hollywood horse wrangler father (Keith David). They know about artifice, and the power of the camera, and respect for wild creatures, having inherited those, too. This is knowledge that should serve them well as they continue the family business. (They claim their ancestor was the unnamed jockey in the first moving picture experiments.) But what’s that in the clouds above? It sure looks like a UFO. The siblings know immediately they need to capture it on film. This self-reflexivity, a movie about moving images, is the engine for a thrilling genre piece—a work of process for how one goes about trying to get an elusive shot, and a work of horror-adjacent sci-fi enchanted by the tantalizing prospect of a big unknown lurking beyond the realm of the possible.

Peele frames many great shots of looking, staring, or averting one’s gaze, with the tall IMAX frames extending beyond characters’ fields of vision, a human face or form one small element in a towering blue expanse. The movie, though small in cast—Brandon Perea, Steven Yeun, and Michael Wincott are the only others of note—and limited in location, has a grandeur of intent and a towering mystery as we watch the skies. As the film slowly unspools its secrets, Peele crafts sequences with hairs-on-the-back-of-the-neck tingling suspense from nothing more than waiting for an element of the image to shift, to reveal new information or for the inscrutable UFO to emerge again.

In the vastness of the movie’s frames, riffing on Western iconography while inviting some vintage Spielberg by way of Carpenter comparisons, Kaluuya and Palmer are given compelling and charismatic characters to inhabit. The sibling interplay is full of loving teasing and real affection, but also the kind of prickly carefulness that can creep into grown familial tensions. There’s a charge from their contrasts. He’s thoughtful, slow to speak, with outer strength covering over his emotional pain. She’s excitable, making schemes within schemes, prone to rattle on and on in good times and bad. We can read all sorts of backstory in what’s not said between them, and the film’s final moments are a satisfying snap as their connection is suddenly drawn tight.

Peele builds to a simultaneous crescendo of character, theme, story, and style, and suddenly the mystery of it all is solved with answers that retroactively make every stray detail and detour lock into place. Peele’s honed his craft to make, if not his most powerful movie yet, his tightest and least immediately obvious in a still-entertaining package. Here’s a movie about our modern tendency to want the enormity of our world’s traumas reduced to the size of a screen—to process through gawking spectacle instead of crying through catastrophes. Instead of bringing us closer together, it can pull us further apart. So here’s Nope, with its grieving siblings confronted with enormous problems beyond the terrestrial norm. Can they survive long enough to get a picture? Maybe. Will that give them control over the situation? You can answer that in a single word. Guess which one.

Showing posts with label Keith David. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Keith David. Show all posts

Wednesday, August 3, 2022

Saturday, May 21, 2016

On the Case: THE NICE GUYS

The Nice Guys is a

good old-fashioned 70’s-style detective movie: loose, swaggering, hilarious,

exciting, shaggy, and involving. A big crowd-pleaser of a period piece, it

creates a convincing vintage stage on which to play out its antics, which

happen to add up to one of the most compelling mystery plots in recent memory.

Sharply directed and wittily written, think of it as the faster, dumber (in a

good way), energetic pop flip side to Paul Thomas Anderson’s hazy Inherent Vice. It is impeccably mounted

and high on 1977 Los Angeles detail. Pants are tight, morals are loose,

wardrobes are bright, the oldies are current hits, cigarette smoke and polluted

smog fills the air, and a low-level simmer of cynicism is everyone’s emotional

baseline. It’s the perfect seedy environment for two low-level mismatched

unlikely partners to stumble into a big conspiracy and try to sort it all out,

and line their pockets, before the bad guys get worse.

The reluctant duo in a buddy action comedy is filmmaker

Shane Black’s preferred dynamic, running through works he wrote (Lethal Weapon, The Long Kiss Goodnight) and directed (Kiss Kiss Bang Bang, Iron Man

3). But it has never been better expressed than here. One is a private eye

hired to track down a missing girl. The other is an unlicensed freelance tough

hired by said girl to stop those searching for her. Events go south and get

shady, so the two decide to work together to unravel the whole nasty tangle in

which they’ve found themselves. Someone (or several someones) else is after the

girl, and she has her own suspicious reasons to remain missing. In typical

pulpy mystery fashion, the men wander through a story full of clues and qualms

provided by an array of eccentric and unseemly types played by an exquisitely

memorable ensemble, while the center holds around the electric grumbling

chemistry between our incompatible, but secretly super compatible, leads. It’s

great fun.

Russell Crowe plays the tough guy. It is one of his finest

performances, a lumbering physical presence with light and lithe comedic

timing. He carries a Wallace Beery weight and gravitas, growling and tough, a

heavy heavy, but soulful and wounded. He’s lonely and a loner, and a little sad

about how alive brawling and tussling with bad men makes him feel. Even worse,

he starts to feel a kinship with his unexpected partner. He’s Ryan Gosling as

more a con man than a P.I., taking sweet little old ladies’ money for easy

jobs. (One widow wants to know where her husband, “missing since the funeral,”

is; Gosling glances at the urn on her mantle and solemnly promises to cash her

check and find him.) He’s a squeaky, lean, scared, in-over-his-head scrambler,

getting by with luck and happenstance. But he’s still sharp enough to piece

together clues with the help of his precocious potty-mouthed 13-year-old

daughter (Angourie Rice) who loves spending time with him, driving him around

when he’s too buzzed to do it himself, which is often. He, too, is loath to

admit that he’s found a new pal.

Together Crowe and Gosling, playing to and against type (a

neat, compelling trick of star power), make a fine pairing – the straight-faced

serious guy, and the flailing comic. They’re bickering and bumbling through a

rough-and-tumble plot full of gumshoe incident and interestingly loopy

interrogations often spilling over into pratfalls and slapstick stuntwork as

malcontents, scumbags, and suspects cause trouble. There are gunfights and car

chases, and plenty of instances of people falling out windows or rolling down

hills. A vast scheme unravels in knots as a large cast (including Margaret

Qualley, Kim Basinger, Keith David, Jack Kilmer, Lois Smith, Matt Bomer, and

Yaya DaCosta among the recognizable faces) stringing along the various episodes

from one clue to the next. Then, with shrewd timing, the story reaches

surprising and satisfying roundabouts that spin the investigation off in fresh

directions. To even suggest the shape it ultimately takes would be unfair to

the film’s brilliantly structured sense of discovery. It eventually involves

pornographers, eco-activists, experimental filmmakers, hitmen, Detroit auto

execs, and the justice department, arriving at immensely satisfying smash-bang

conclusions as every moving part clicks into pleasing place.

A deeply satisfying work of genre fiction, The Nice Guys is an engaging and

confident trash beauty, with handsome nostalgia surfaces in slick frames

provided by cinematographer Philippe Rousselot polishing a cavalcade of

violence, nudity, swearing, and seamy underworld spelunking. All that

is mixed in a screenplay flowing with wordy personality and hilarious physical

beats, and story unfolding so cleverly that as its bighearted love for its

characters’ connection sneaks in sideways it sweetens the suspense with genuine

feeling. We want them to crack the case, but also become better people by

learning to work with a new friend. It’s delightful even as it is brutal, a

hard-charging lark. So fast and funny, driven by charismatic performances and

compelling mystery, this somehow manages the trick of making the old new again.

It’s at once sturdy throwback appeal and a fresh spin on material that could be

tired, but isn’t here. Black’s preoccupations with bantering buddy dynamics

expressed through action and intrigue are given their purest, most complete

expression. This is a groovy, most completely enjoyable action comedy.

Monday, October 29, 2012

What is Any Ocean but a Multitude of Drops? CLOUD ATLAS

Starting with nothing less than a Homeric incantation in

which a white-haired old man stares into a crackling fire and seems to summon

the fiction into being, Cloud Atlas, an ambitious adaptation of David

Mitchell’s tricky novel, is the kind of movie that’s easy to recommend and

admire, if for no other reason than that nothing quite like it has ever existed

and is unlikely to come around again any time soon. It wobbles at times, but luckily

it’s ultimately better than the sum of its gimmicks. This is a complicated film

about simple truths: love, ambition, knowledge, power. A major motif is a

musical composition that one of the characters writes called “The Cloud Atlas

Sextet.” It’s a lush, haunting piece of music that winds its way through the

soundtrack and, by its very nature, echoes the major structural conceit of the

film. A sextet is a piece of music to be played by six musicians. This film –

like the novel before it – contains six stories, any one of which could easily

expand into its own film, but together combine into one gorgeous whole.

Spanning centuries and genres, the film breaks apart the

book’s chronological and mirrored presentation and instead places the six

stories parallel to each other, cutting between the stories with a gleeful, witty,

dexterous montage that recalls D.W. Griffith’s 1916 feature Intolerance in the way it so skillfully

weaves in and out of varying plotlines. A massive undertaking, three directors,

Tom Tykwer (of Run Lola Run and Perfume: The Story of a Murderer) and

Lana and Andy Wachowski (of The Matrix

films and Speed Racer) split the six

sections among them, adapting and directing separately but from a shared common

vision so that the story flows both stylistically and emotionally. Like some

strange geometric object with many sides and layers, the film grows all the

more epic by expanding outwards through time and space.

It takes us to the Pacific Ocean in the nineteenth century

aboard a ship sailing towards America. Then, we’re in Europe in the 1930s, following

a disinherited, but ambitious and talented, music student to the home of an

elderly composer. Next, we’re in 1970s America, following an intrepid reporter

into a conspiracy at a new nuclear power plant. On to the present, where we

find a publisher who is the victim of a mean brotherly prank and stuck in an

unexpected place. Then we’re to the future, where a clone slave describes her

story of finding awareness of the consumerist dystopia she lives in. Finally,

to the far future, where we find a post-apocalyptic world that has returned to

clannish living in the wilderness, where the peaceful people are terrorized by

a tribe of aggressive cannibals. Tykwer and the Wachowskis present each setting

with handsomely realized production design and detailed special effects. Moving

between them is anything but disorienting; it’s, more often than not,

invigorating.

Almost too much to handle in one sitting, this film is a

rush of character and incident, themes and patterns, echoes upon echoes, all

distinctive melodies that fade and reoccur time and again. Some sequences play

more successfully than others, but the film is largely fascinating and

generally gripping as it becomes a symphony of imagery and genre, returning

again and again to mistakes humankind makes, the benefits and constraints of

orderly society, and the way underdogs try to find the right thing to do

against all odds. The themes play out repeatedly in a flurry of glancingly interconnected

genre variations. What appears as drama later plays as comedy, as action, as

mystery, as tragedy. Tykwer and the Wachowskis have put the film together in

such a way that the editing escalates with the intensity of each plotline,

bouncing in an echoing flurry during rhyming plot points (escapes, reversals of

fortune, setbacks, reunions) and settling down for more languid idylls when the

plots simply simmer along. By turns thrilling, romantic, disturbing,

suspenseful, and sexy, there’s a fluidity here that makes this a breathless three-hour

experience. The film moves smoothly and sharply between six richly imagined

stories that connect more spiritually and metaphysically than they do

literally, and yet artifacts of one story may appear in another, sets may be

redressed for maximum déjà vu, characters in one story may dream glimpses of

another. This isn’t a puzzle to be solved, but rather a stylish assertion that

people are inescapably connected to their circumstances and to those who lived

before and will live after.

In order to underline its insistence upon the connectedness

of mankind then, now, and always, the film features the same cast in each

story, making it possible to get a sense of the progression of a soul through

time, each reincarnation living up (or down) to the example of earlier

experiences and choices. Through mostly convincing makeup, actors cross all

manner of conventions, playing not just against type, but crossing race, gender,

age, and sexual orientation in unexpected ways. (Some of the biggest pleasant

surprises in the film are in the end credits, so I’ll attempt to preserve them.)

For example, Tom Hanks appears as a crackpot doctor, then again as a thuggish

wannabe writer, then again as a haunted future tribesman, among other roles.

This is a large, talented and eclectic cast with Halle Berry, Jim Broadbent,

Hugo Weaving, Keith David, Doona Bae, Jim Sturgess, Ben Whishaw, James D’Arcy, David

Gyasi, Susan Sarandon and Hugh Grant delivering strong performances, appearing

over and over, sometimes obviously, sometimes unrecognizably or for only a

moment. This allows the filmmakers to dovetail the storylines even further, for

what is denied in one (lovers torn apart, say) may be given back in the space

of an edit (lovers, not the same people, but played by the same performers,

reunited).

Though some will undoubtedly be turned away by its earnest

(if vague) spirituality and messy philosophical bombast, this is the kind of

film that, if you let it, opens up an endless spiral of deep thoughts. You

could think it over and spin theories about what it all means for hours. To me,

that’s part of the fun. It’s a historical drama, a romance, a mystery, a sci-fi

epic, a comedy, and a post-apocalyptic fantasy all at once. In placing them all

in the same film and running them concurrently Tykwer and the Wachowskis have

created a moving and exciting epic that seems to circle human nature as each

iteration finds characters struggling against societal conventions to do the

right thing. The powerful scheme and rationalize ways to stay on top; those

below them yearn for greater freedom and greater meaning. There’s much talk

about connection and kindred spirits; at one point a character idly wonders why

“we keep making the same mistakes…” It accumulates more than it coheres, and

yet that’s the bold, beautiful mystery of Cloud

Atlas, that it invites a viewer into a swirl of imagery, genre, and

character, to be dazzled by virtuosic acting and effective filmmaking, to get

lost amongst the connections and coincidences, to enjoy and perhaps be moved by

the shapes and patterns formed by souls drifting through time and space.

Saturday, January 16, 2010

Almost There: THE PRINCESS AND THE FROG

It was a sad day when it was announced in 2004 that the pretty awful Home on the Range would be the Walt Disney Company’s last work of hand-drawn animation. The medium responsible for all of that studio’s greatest artistic achievements, from Snow White and Pinocchio to Beauty and the Beast and The Lion King, was being thrown overboard in order to better jump on the CG bandwagon, a wagon that was already plenty full with Pixar, Dreamworks, Sony and BlueSky, among others. So it is a relief to see The Princess and the Frog, Disney’s return to what they do best, classical storytelling with hand-drawn style. Sure enough, the film doesn’t disappoint on the visual front, each frame filled with fluid beauty that resonates with equal parts wonder and nostalgia. The mild failings of the movie have been left to fall solely on the storytelling.

Featuring the first black princess in the company’s history (about time!), the story is a smart, if a little derivative, retelling of the Prince who becomes a frog and must be kissed to reverse the spell. The voice work is uniformly excellent with Anika Noni Rose and Bruno Campos as thoroughly delightful leads. The leads are thoroughly charming; the prince dances like Gene Kelly and the princess has a weary grace about her. You see, she’s not actually a princess, but rather a hard-working waitress mistaken for a princess by the frog prince when he stumbles upon her at a masquerade ball on the first night of Mardi Gras. The film takes place in a lovingly recreated 1920’s New Orleans, with zydeco and jazz influencing Randy Newman’s soundtrack and Cajun cooking practically wafting off the screen. It’s an enchanting location for a sweet little adventure, especially since, not being a princess, she becomes a frog post-kiss and the two of them escape to the bayou.

At times though, the thrust of the story is lost amidst the strain of the Disney folks stretching their artistic muscles to the point where it feels like the creative team is working off of a checklist of classic Disney features. There’s an overflow of fully animated musical numbers and, while many are charming and striking, they trip over each other and too few really stick. There are more than enough charming animal sidekicks (a dog, a turtle, a gator, a family of fireflies) and plenty of human types as well (people fat and skinny, tall and short, snaky and prim, white and black, smart and hick). It’s nice to see that the Disney animators have such a wide range of skill in producing so many of the character types that have been used in the past, but were they all needed in the same picture?

So, the movie’s a little busy and at times frantic or just plain unmemorable and the plot muddles a bit more than necessary, but I barely care. There are a host of wonderful moments as well, times where the plot zigs where hundreds of animated features have always zagged and quiet character moments that are genuinely touching. There’s also a memorable villain in the form of a voodoo witchdoctor (Keith David) who gets the most memorable song and some genuinely creepy henchmen. And, above all, I like the leads. They were well-voiced, well-designed, and easy to care about. I only wish they weren’t frogs for so much of the film; they make much more appealing humans.

Now get back to work, you fine folk of Disney. I’m ready for another hand-drawn masterpiece from you.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)